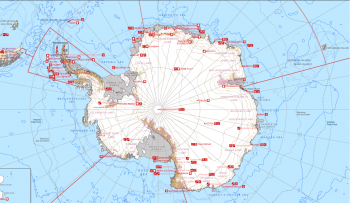

Most of the research sites are located on the Peninsula, followed by the coast. Credits: www.comnap.aq

Dr. Carmen Possnig is the ESA-sponsored medical doctor spending 12 months at Concordia research station in Antarctica. She facilitates a number of experiments on the effects of isolation, light deprivation, and extreme temperatures on the human body and mind. In the following post, Carmen discusses sleep disruption in Antarctica.

Antarctica is often described as the most isolated place on Earth. The coldest, windiest, driest, highest continent, and one of the hardest places to live and work. 28 different nations have research stations here, spread over more than 14 million square kilometres, most of them on the coast. Of the permanently occupied stations, only three are located within the continent – Amundsen-Scott directly at the South Pole (USA), Vostok (Russia), and Concordia (us!).

One of the factors that can make life here harder, and for some even becomes an obsession, is sleep. Even the earliest Antarctic expeditions report that sleep problems were frequent and problematic: both for physical well-being and for crew morale.

A trigger for these problems are the unfamiliar light conditions – in summer 3,5 months of continuous sunlight, followed by a few weeks of halfway “normal” day/night cycles, long twilight periods and finally 3,5 months of complete darkness. But we need normal day/night cycles as so-called timers: this regulates our circadian rhythms, the “inner clocks”, which are followed by many physiological, psychological and behavioural parameters, such as body temperature, production of corticosteroids, melatonin release, cardiovascular functions, alertness, mood and memory.

If one is isolated from these timers, including social factors and meal times, our circadian rhythm tends to shift and settle down at about 25,4 hours. The sleep-wake rhythm can therefore wander almost ten hours a week.

After a waking night of croissant baking: Moreno and Carmen besiege the sofa. Credits: ESA/IPEV/PNRA– F. Cali Quaglia

If you are exposed to normal conditions again, the internal clock synchronizes itself back to the external reference points.

The crew at polar research stations and space stations live without these timers, which are important to reset the physiological clock. While people at the poles live in complete darkness or twilight for more than half of the year, astronauts in low Earth orbit have more than a dozen sunrises and sunsets every day. Lunar days and nights are each 28 Earth days long. Mars, on the other hand, would have a 24,4 h day, similar to Earth. Mars and Earth also have a similar sequence of seasons, since the polar axes are tilted almost identically.

Back to Antarctica.

Here, similar to jetlag, our 24-hour rhythms are not synchronized with our sleep times. However, our sleep rhythm is determined by working hours and meal times.

In comparison to stations on the coast, Concordia is regularly at the forefront of various sleep studies when it comes to sleep problems. The hypobaric hypoxia here seems to have a greater effect on us than the shifted light cycles do.

The effects: a strong reduction of the deep sleep phases, sometimes even complete absence; increase of REM phases; poor sleep efficiency, meaning longer fall asleep time and more frequent waking up during sleep; and changes in sleep-breathing.

Physical activity could possibly help: isolation and confinement cause people to move less, and accordingly there is no accumulated fatigue in the evening. But here, with hypoxia, it is not a good idea to exercise especially in the evening – it changes sleep breathing even more and triggers periodic breathing phases. Accordingly, we sleep even worse.

We have different types of sleepers in Concordia:

• people who sleep all night and half a day and then come to lunch for the first time;

• people who find it impossible to sleep at night and who are happy to spend 2-3 hours in bed in the morning;

• people who sleep relatively normal 6-8 hours.

What they all have in common: we rarely feel well rested in the morning. We are permanently a bit sleepy. We constantly feel a sleep deficit, with all the associated concentration problems.

The relationship between psychological symptoms, sleep disorders, circadian disorders and general psychological adaptation cannot yet be fully explained. But we would all be happy if there were more research in this field, also with regards to future space missions in which astronauts will certainly struggle with similar problems as we have here at Dome C.

To read Carmen’s adventures at Concordia in German, see her personal blog.

Discussion: no comments