Dr. Carmen Possnig is the ESA-sponsored medical doctor spending 12 months at Concordia research station in Antarctica. She facilitates a number of experiments on the effects of isolation, light deprivation, and extreme temperatures on the human body and mind. In the following post, Carmen discusses transportation in Antarctica.

What is the most efficient way to bring material into the Antarctic interior?

Robert Falcon Scott already tried his luck with motorized companions – he was looking for an alternative to his ponies and dogs. His engines didn’t get very far – a few kilometres over the Ross Ice Shelf.

Airplanes land here far too rarely. Sending a plane over, depending on the weather, is dangerous and expensive. All equipment, food supplies, fuel and baggage of the hibernators are delivered across the continent with the help of a traverse from the Antarctic coast.

From Cap Prud’homme (near Dumont d’Urville, the French station on the Antarctic coast), the traverse starts 2-3 times a summer to Dome C. In 1993, the French Antarctic programme reached Concordia for the first time under the technical direction of Patrice Godon, who is also known as the person who has covered the largest distance in Antarctica.

Since the 1950s the Russians also use traverses to supply their station Vostok. Since 2005, an American traverse has connected McMurdo with the third permanent station within Antarctica, Amundsen-Scott.

Driving in the snow. One Challenger drives ahead and pulls a second one with a thick rope. The two have to drive at exactly the same speed. Credits: ESA/IPEV/PNRA–C. Possnig

A traverse consists of several sledge trains, each towed by a Challenger caterpillar tractor that runs at 7-18km/h depending on snow and weather, specially adapted to the conditions of the Antarctic high plateau.

At the very front a cash drill drives to find the way, to level the ground and to create a small snow wall at the side, so that one makes easier progress on the way back. Although it never gets dark in the Antarctic summer, most vehicles have powerful headlights so as not to get lost in the event of a white out.

The Challenger pulls containers of various contents onto sledges, to say the least. In addition to fuel, equipment and food containers, there is also a living module with kitchen, satellite radio and driver berths, and a module with a workshop, snowmelt and toilets.

The crew usually consists of 10 people, half of them mechanics, and everyone is at the wheel of a vehicle. The caterpillar drives for approximately 14 hours a day, if the weather allows it. That means a distance of approximately 100 to 120 km a day.

The fuel supply to the traverse has to be calculated meticulously so as not to get stuck anywhere in the middle of nowhere – this is what happened with a traverse to Vostok decades ago, whereupon all those involved starved to death.

Between Cap Prud’homme and Concordia the traverse is about 1100km. Every year they try to follow exactly the same path, but this often turns out to be difficult: especially during the first traverse of summer; snowfall and winds make the trail disappear over the winter.

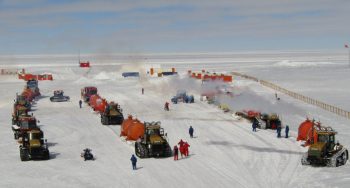

The first traverse reached us on December 24th and mainly brought fuel for the station. Credits: PNRA–M. Giorgioni

The first half of the route is rather problematic. It is hilly, in the soft snow you can can easily get stuck, there are wind storms and the danger of driving into a crevasse. Sometimes the most dangerous areas are explored by helicopter beforehand. A large area of about 200km from the coast is circumnavigated. When the traverse meets a crevasse, there are two possibilities: driving around or shoveling up with snow – and both operations are time-consuming.

The further south you go, the easier the trip is – no more crevasses, the snow more stable, the way easier to find.

On the way back, the only thing being transported is our waste. Most of this is then shipped to Australia or, in some cases, to France, where it is recycled. It can take two years between the generation of waste here and the final supply.

The second traverse reached us at the end of January. This time there was more fuel, lots of food, lots of equipment for the experiments and our personal luggage. A container, which is constantly warmed up to +4°C, is specially reserved for luggage – nevertheless, everyone checks the wine and whisky bottles for frostbite first, and I somewhat try nervously whether my stage piano survived the long way (yes, it did).

Here at Concordia we follow the progress of the traverse on the radio for days. We jump enthusiastically on skidoos and bikes and drive towards them.

We stand somewhere in the white desert and see the snow-capped Challenger stomp past us, one after the other pulling a row of containers, and in each cockpit a new, friendly smiling face.

To read Carmen’s adventures at Concordia in German, see her personal blog.

Discussion: no comments