Some things change you forever. They put your life on a trajectory you had never planned, different from those of all your friends – and you are propelled into adventure.

I was just a young girl growing up in rural Herefordshire, England. Playing in the fields, feeding the geese, running around – laughing a lot over a little – with my friends. That was my world. But at 15 years old, life struck me, Beth Healey, so hard that I would never look at it the same way.

I lost one of my closest friends in a car accident.

Suddenly I understood what people meant by “you only live once”.

I also realised that no one is immortal, that cliché sayings like “life is a precious thing” in the end are true, and that we never know how long our life will last.

Maybe that was part of the reason why I would later start medical school and become a doctor. I worked in the Accident and Emergency department of Chelsea and Westminster Hospital in London. There I saw how short life really can be, but also that lives can be saved.

Treasure life and make it count, I told myself. If you have an opportunity, go for it.

This inclination of mine to try and live life to its fullest – perhaps my fear of missing out on the best things in life – would lead me on a number of adventures. One of them far, far from my native England…

I have always enjoyed being outdoors and going on adventures. This started with family ski holidays in Norway, where I had my first experience of real cold. Trips to the Alps followed, and in medical school it felt like a natural progression to start to explore the world of Expedition and Wilderness medicine. I also developed a growing passion for research as a student involved in pre-hospital care. I was particularly interested in how the human body and mind respond to extreme conditions. This was something I would get use of in ways I had never planned.

[pullquote]The last great wilderness, an area larger than Europe, and with an environment so hostile that still today no country owns it.[/pullquote]

I always felt a special thrill thinking about the famous explorers of the world. Polar exploration in particular thrilled me. The expeditions to the South Pole of Amundsen, who managed to return safe and sound with all his men, and of Scott, who was never to return from the Antarctic, fascinated me. Much had happened since these early days of polar exploration, not least thanks to technological developments, but still there were places on that southernmost continent that remained unvisited by anyone.

Driven by such thoughts, I became a fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, which supports and promotes geography and related research, education, fieldwork and expeditions. At the Society’s premises in London I met many people who had not only travelled the world but been on expeditions to the most remote corners of it. That was when and where the name of Antarctica took on a particular significance for me. There was a special meaning and weight to the word.

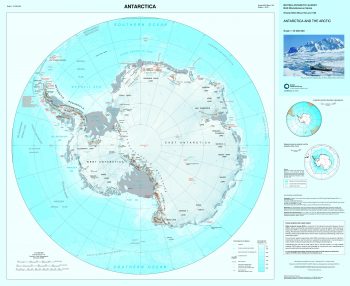

Antarctica, this continent unlike any other at the end of the world. The last great wilderness, an area larger than Europe, and with an environment so hostile that still today no country owns it. Instead it is governed through an international treaty safeguarding its vast frigid deserts for the aims of peace and science for anyone brave enough to tread its ice.

Somehow, the continent was calling me. And intriguingly enough for me, my fellows at the Royal Geographical Society all told me it was achievable to one day go there and stay through a full Antarctic winter. If I decided on it and was willing to follow my ambition.

However much I doubted my chances and capabilities for such an enterprise, I knew that I wanted to go. A seed had been planted. But it would not be easy. I had to find a way, a place in one of the few crews, also of very limited size, that were selected once a year for such an overwintering experience.

My chance came through the European Space Agency, of all possible organisations. It all started with ESA organising a workshop on space medicine at the European Astronaut Centre in Cologne. After writing an essay to win my place, I found myself greeted by the many flags at the entranceway to the centre. During the following fascinating days I learned about medicine linked to space and was inspired by the people I met there. Most of all by the new ESA astronaut Tim Peake from the UK, who told us about the mission he was getting ready for on the International Space Station. The experience opened my eyes to the world of space, as the last true frontier for exploration.

It was three years later that I saw the ESA call for a position to work in Antarctica. I was at that time up working in Greenland. The position was as medical doctor to run physiological and psychological experiments on the crew at the Concordia research station. ESA was studying the effects of living in an extreme environment, as this was similar in many ways to a mission in space, and the crew needed “to be prepared for anything”.

I was just completing my Junior Doctor years and was hoping to spend the coming year following my interest in research. I also wanted to combine that with the opportunity to travel while doing something interesting and different. So the ESA position was an opportunity for me, for sure. This truly exotic posting would be a real challenge and keep me well occupied with fascinating research experiments. Besides, it would be a real polar adventure.

[pullquote]In terms of both distance and travel time, Concordia is more remote than even the International Space Station.[/pullquote]

The risks of living at a station as remote as Concordia are real and did require some consideration. Concordia is a French-Italian research station situated 1200 km inland on the Antarctic continent. It sits 3200 metres high up on an ice mountain plateau. It is one of the few truly isolated stations where evacuation is impossible for nine winter months even in case of emergency, as temperatures are too low for planes or helicopters to function and thus for anyone to reach the station. The air on the plateau drops to -80C during winter. As if that was not enough, it is also so thin that breathing it is a challenge on its own. In such an environment, even an apparently minor problem can escalate quickly. It is strange to think that in terms of both distance and travel time, Concordia is more remote than even the International Space Station. Even during summer when planes can access Concordia, astronauts on the Space Station have a much shorter evacuation time. The possibility that something could go wrong during such a stay was indeed at the back of my mind, but I would not let it deter me from trying my luck.

Concordia station – in terms of both distance and travel time even more remote than the International Space Station.

But would I be up to the task? The position of medical doctor there also came with responsibility for leading the medical rescue team. If I got the chance, I would have to live up to the responsibility. I sometimes find it hard to stand up for myself – would I be able to deal with everything such an expedition might throw at me?

I do not fit what most people imagine for a polar scientist. My friends have described me as a tiny blondish girl, bustling with energy, but who likes it cosy. I will always remember the look of surprise I got the first time I went out to meet an expedition group in Greenland and took off my helmet. Not what they had expected at all…

[pullquote]The look of surprise I got when I took off my helmet. Not what they had expected at all… [/pullquote]

I am 28 years old and like what many girls my age do – shopping and getting a good haircut, and I don’t mind a nice spa treatment once in a while. These features are generally not considered well suited to life in a polar environment. However, I do not see why that has to be the case (although admittedly shopping may have to wait, spas will be run on a very individual basis and a decent hairdresser may be the last of your preoccupations at -80C). It is true, I am not built for minus 80 degrees cold, but then, who is really? So why should not I, Beth Healey, go polar for real?

However full of doubts I was, deep down I knew that I had to be on that southbound plane should I get the chance.

Of course I sent in my application.

As I am still a relatively junior doctor I thought there was a considerable risk that my application would be turned down. On the other hand, I already had experience of working in remote environments in northern climes and in expedition medicine. The biggest challenge with this position was not really the research itself but rather to continue to perform well in extreme conditions.

I passed the first step in the selection procedure when I was called, with the other selected candidates, for interviews in Paris. The Eurostar train brought me quickly and smoothly under the Channel to the French capital, but for me the trip seemed to take forever and was not really so pleasant as I was quite nervous. It was good that after arrival, the day before interviews, we had the chance to talk to previous medical doctors who had been working for ESA at Concordia. This would make sure we understood what we were getting ourselves into and what the job would entail.

[pullquote]The goal of going to such a remote place is really to act as a kind of envoy for humankind and bring back knowledge.[/pullquote]

I was quite excited about the possibility of leading research experiments in preparation of human spaceflight activities. Much of this seemed rather futuristic, such as enabling astronauts to work and live for longer periods on the Moon or even on Mars. But I was also motivated by Antarctica being such an emblematic location for understanding our own planet’s environment and climate. A research station like Concordia is used for so many different fields of study, from seismology to astronomy. The goal of going to such a remote place is really to act as a kind of envoy for humankind and bring back knowledge that would be hard or impossible to get back at home. I was convinced this would benefit not only astronauts in space, but common people here on Earth as well, linked to environmental and health care aspects for example. In my professional role as a medical doctor I could certainly learn a lot of use for my future work with patients.

Enabling astronauts to work and live for longer periods on the Moon or even on Mars is one goal of ESA’s research activities in Antarctica

So the talks with the previous medical doctors only strengthened my resolve. I knew, however, that I would have to convince the interview panel that I was the right person for this unique position.

On the morning of the interviews we all had an intensive medical examination. My nervousness was heightened when I realised I had accidentally taken a skinny latte and croissant before the fasting blood test that morning. Great start!

After medicals I finally went in front of the interview panel that had representatives from both ESA and the French polar institute IPEV. The panel laid out to me the basics of the experiments I was expected to run, and more importantly that I would have to spend one year confined to the Concordia station, with the long polar winter in complete darkness as the Sun would never rise. I would in other words face not only ice, but isolation.

I had expected a grilling from the panel and I got my fair share of questions, but I was almost relieved to get the chance to discuss the potential problems one could be facing in such a remote and harsh environment. My past experiences with groups in Greenland helped me in this respect.

But I was not to be let off the barbecue just yet as the interview was followed by an intensive psychological examination.

Completely exhausted by the end of the day, I fell straight into bed.

The waiting game had begun. Returning to London, I felt that I had done all I could. At least I sincerely hoped that I would be up to the task of handling such a position.

But there was one shadow lingering at the back of my mind, on the borderline between the professional and the private. I could not know how I would react and change during many months of isolation, with no escape possible. I knew full well that people changed under pressure, living in a single crew confined to a single place. Darkness, isolation and an extreme environment, maybe combined with unforeseen stressful situations, would be hard on the mind for anyone. There had been a case of severe problems at one Antarctic station in the 90s, where the crew mutinied, refusing to follow orders from their commander. Thoughts about psychological problems, the fear of losing my mind, raced through my head. But the only way to find out how I would react would be to endure a full stay.

I saw the message arrive in my email inbox one morning while I was on the phone and getting ready for work. Swallowing once, I opened it without further hesitation – and started jumping around my flat in elation. I was selected! My flatmates must have thought I had lost the plot, but as I passed on the news they started jumping with me.

Now things moved quickly. After accepting the position, there was not really time to catch breath, never mind to worry too much.

As part of my training, I soon got to spend one week in Chamonix in the French Alps. This was to meet all the French medical doctors going to work in a clinical capacity in various places in Antarctica that year. We learnt about the management of altitude sickness due to lack of oxygen, patient retrieval, frostbite, mountain medicine and hypothermia (i.e. your body getting dangerously cold). The training also involved time staying in mountain huts and on the glacier. It felt fantastic to spend time with so many experts in the field and to get more confident working as a doctor in difficult environments.

I visited the European Astronaut Centre in Cologne to learn more about the research I would be carrying out. There I had the opportunity to meet all the “Principal Investigators”, i.e. the research group leaders for each ESA experiment that would be carried out at Concordia. It was a strange feeling to prepare to be their “hands, eyes and ears” on the other side of the planet, remotely carrying out their experiments to bring the sought-after data back to Europe.

In order to take baseline data measurements for the ESA protocols, I wandered around the centre with lots of equipment strapped on, including 24-hour blood pressure monitors, saliva samples and urine bottles. Examinations included blood tests, functional magnetic resonance imaging scans, cognition tests, for starters. A baptism of fire!

In fact, the whole Concordia overwinter crew had been invited to the Astronaut Centre for a special Human Behaviour Performance training. This was the same training astronauts receive before going to live on the International Space Station. We were a group of 13 people, including me, predominantly of French and Italian nationality, nine men and four women. I was nervous about meeting these people I would spend so much time together with, but enjoyed meeting everyone for the first time. We learned about how to work together as a team and some of the challenges we might face living in such a small group for a long period of time. We also started to identify our own personality traits and those of team members to help us identify potential problems early.

In addition, we were able to explore the Space Station training modules and the neutral buoyancy pool where the astronauts train underwater. During this tour we had a very special meeting: ESA astronaut Samantha Cristoforetti, from Italy, gave us advice just before she left for her mission to the Space Station. She kindly gave me a keyring with her preferred motto engraved on it: “Don’t panic”. I carefully tucked the little object away for future use and decided to adopt the motto for my own coming mission as well.

[pullquote]She gave me a key ring with her preferred motto engraved on it: “Don’t panic”.[/pullquote]

Back in the UK, I continued the preparations for my departure – including the more personal matters. I knew a small number of people who had already overwintered in Antarctica with the British Antarctic Survey. They helped to prepare me, telling me about their experiences and the challenges they had faced. They also helped me on a practical basis – like telling me how many tubes of toothpaste to pack for a full year. They talked fondly of traditional Antarctic events, like the Midwinter celebrations I would soon get to enjoy, and this helped dispel some of my fears.

Family, friends and a number of earlier colleagues also gave me support and encouraagement. Those closest to me said I was fit for the challenge and that this was the right path for me. I hoped they were right.

[pullquote]While my friends all seemed to be buying bikinis, I was busy buying bobble hats.[/pullquote]

Some of my friends were going abroad to work in Australia and New Zealand. If I had not decided to go to Concordia I would most likely have joined them. So while my friends all seemed to be buying bikinis, I was busy buying bobble hats.

I said bittersweet goodbyes to my closest friends knowing I was not going to see them for at least a year. With my family I enjoyed an “early Christmas” in November (the full works, including turkey, presents, tree and crackers) and later a rather fitting farewell celebration at the “Ice Bar” in London.

The plane would leave from Paris so, alone, I took the train there. Antarctica could not have felt more distant as I walked the bustling city streets. My last night in Europe I spent at a close friend’s place. I remember stroking her cats just before I left for the final departure. I would not see an animal in over a year and would almost forget the sensation of soft fluffy hair passing through my fingers. Where I was going, there were no animals. There would only be our small crew, alone in that remote research station.

It was time to face Antarctica.

Discussion: one comment

I am grappling with the behaviour of extra-terrestrial communities both in my academic and creative writing (I shouldn’t try to sell them here!). So I recognise your comment “Antarctica being such an emblematic location…”

Michel Foucault describes such functional places as heterotopia, so I think one of the early questions about a truly extra-terrestrial community will be whether it is a place defined by function (e.g. a Helium-3 mine, or a colony) or defined as a location in itself (eg Rome, Paris, London).

Foucault also leads to a useful discussion about power and discipline in extra-terrestrial communities, and perhaps this is where the behaviour training module fits in – at least until Concordia declares independence!

I intend to engage with Foucault’s work on government (and that of Juergen Habermas on democracy) in my future examination of extra-terrestrial communities. So I am also intrigued by the multi-nationality of Concordia, and the supra-national supervison, in this case by ESA.

So there is a great deal of political philosophy in this work, and I look forward to the next instalments. Many thanks.