Concordia felt like a different place to that I had called home just a few weeks before. It was the height of summer, so the station was really busy. Decorations from celebrations I had not been part of lay around looking tired. I also did not know most of the faces there anymore. For me it really did feel like the party was over and that it was time to leave. Although I felt apprehensive about my coming reintroduction into society and my unclear future, I was now ready to say goodbye. I took that final plane out the following morning.

Back again at the Mario Zucchelli coastal station a ship was waiting to take me on the long journey from Antarctica to New Zealand. There a long-time friend would be waiting to meet me. I had planned my return to the outside world in stages like this, and would spend a few weeks in New Zealand with my friend, slowly getting re-accustomed to the ways of the outside world.

[pullquote]As I restarted my life, I had forgotten what it was like to use a mobile phone or a debit card. [/pullquote]

This proved to be quite helpful. As I restarted my life – now as a tourist – I had forgotten what it was like to use a mobile phone or a debit card. In fact, my phone number had been cut off as I had not used it for over twelve months, and it took a few sweaty trials to get my PIN code straight again. Socially I had lost most of my confidence and found myself hiding behind my friend when we were booking into hotels or ordering food. It took time to readjust. I think that for people who left Concordia with the first plane out of winter, heading directly to a busy airport and Europe, the shock must have been much more pronounced.

Even using money felt out of place for a time. At Concordia I had lived in a world without money, where everyone had the same clothes and access to the same things, taking away much of the social class system and putting everyone on a level playing field. It had been almost like a social experiment – and that was an experiment I had never assumed I would be part of.

[pullquote]I had not been shopping for over a year, and had not missed it nearly as much as I thought I would. [/pullquote]

This had also made me realise how unimportant many consumer products are and how you can make do with the same things for a long period of time. I had not been shopping for over a year, and had not missed it nearly as much as I thought I would. Not anymore having a clue what the latest smart phone should look like, neither did I really care. Life in Antarctica had given me the time to appreciate the smaller things in life, like having a tea break with friends or being creative and drawing a picture.

Having lived without plants and trees for over a year also made me appreciate nature all the more. Many times I must have been staring in wonder like a baby on this rediscovered world full of new smells and colours.

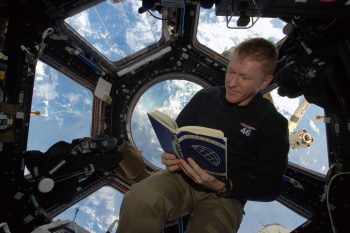

Similar to what astronauts on the ISS must feel, Concordia felt so far from the real world that you were no longer part of the Earth. Credits: ESA/NASA

In something similar to what astronauts on the International Space Station must feel, Concordia felt so far from the real world that you were no longer part of the Earth. This outside perspective let me look back and evaluate my priorities and direction – a contemplative “time-out” from the normal course of my life.

As I finally took leave of New Zealand and started on my flight back to Europe I had all these thoughts in my head, but most of all I looked forward to see family and old friends again. To come home.

I had experienced such an amazing journey. Seeing the star-filled Antarctic night sky and southern lights is something that will stay with me for the rest of my life. I had got through our period of isolation, met so many different characters, listened to the adventures of the pilots and seasoned Antarctic workers and the overland traverse crew that I had even joined myself. I had carried out a number of exciting science experiments, learning a lot about conducting research, working and living as part of a team. As a doctor I had learned more about retrieval medicine and cold injuries. But above all I had learned so much more about myself.

[pullquote]Above all I had learned so much more about myself. [/pullquote]

When I left I had thought this was a journey to explore Antarctica, but coming home I found it had even more been a journey to explore my inner self.

Over a year ago I had been sent out as an envoy for the research group leaders of our experiments. Now I was coming back with the data from the far side of the world, data that could tell us how the crew members had been affected by our long period of isolation and what kind of bacteria or life forms I had sampled from the snow. It is a real honour to have worked for these scientists at the top of their fields. Regardless of my own experiences, this research made the whole trip worthwhile for me, as the results should bring so many different benefits. Opening new possibilities for astronauts to live and work in space, on the Moon or on Mars, is perhaps the most thrilling side of that. But knowing more about how the human body and psyche react to a harsh environment including darkness, cold and isolation will also bring insights of more general medical use. For example, many people work in artificial light in night-time crews, these coming close to our experimental group. Also, as a medical doctor I could see how many of the human factors of importance for spaceflight are of equal importance in a clinical setting here on Earth.

Undertaking the journey between two so remote parts of our world in fact made me realise how connected they are. Having felt the Antarctic cold bite into my skin made it clear to me that the temperature of air and water down there is something real – and also something changeable, that will always be interlinked with the rest of our planet. All those kilometres of ice we had lived upon are an integral part of the water cycle, including also the oceans, seas, lakes, rain and humidity that I knew from home. It had been humbling to face that extreme environment as a small human being, and it had taught me how wrong it would be to consider something as less important just because it is far from your everyday experience. Antarctica’s delicate balance can affect worldwide climate and sea levels everywhere. In a way we are all connected, all part of this fascinating planet Earth, all dependent upon its environment and climate and natural resources, as well as upon each other. An environment like Antarctica is also dependent upon us and how we treat it.

[pullquote class=”left”]How wrong it would be to consider something as less important just because it is far from your everyday experience. [/pullquote]

It was only back home in the United Kingdom that I fully started to appreciate how unique an experience I had behind me and how this extends much further than myself. Many people were touched when I told them about this journey, many of them total strangers with no involvement in these fields of work. I had grossly underestimated the impact my experience would have on other people, but now I found a real pleasure in sharing my impressions with them. I feel privileged to be involved in outreach and educational activities to share what I had lived through. This is also a way for me to return the favour to those people who inspired me to go on this journey. I would like to encourage more young people, and girls in particular, to enter the fields of science and exploration. I must emphasise that as a girl you do not need to cut off your hair and become “GI Jane” in order to do so – I am proof of that!

[pullquote]As a girl you do not need to cut off your hair and become ‘GI Jane’.[/pullquote]

I do realise that the “Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration” of Scott, Amundsen, Shackleton and the rest is over and that I am not the first person to have visited. Still, I had realised a life-long dream to get through a full winter there. So back at home, in familiar London, did I feel empty and that my adventures were now over, with nowhere to go and nothing to motivate my curiosity any longer, as I had feared?

[pullquote]Instead of feeling empty and at the end of my ambitions, I feel like I am only getting started.[/pullquote]

With only a few weeks of hindsight I was happy to discover that this was far from the case. The links of my research with human spaceflight and space exploration made it dawn on me. I suddenly felt more inspired and motivated than ever. I had found my new frontier – one of true pioneering exploration. I would continue to be a part of the exploration of space!

Beth presenting her adventures during the touring WhiteSpace exhibition, here at the Farnborough International Airshow 2016. Credits: ESA

I had never considered space exploration as something I could take part in. Subconsciously I had dismissed it thinking I would never have the opportunity to go into space. Now I saw things differently. While I may never actually go into space (but who knows?) I realised that I was already – and could continue to be – a part of all the men and women pushing the boundaries of this field. Instead of feeling empty and at the end of my ambitions, today I instead feel like I am only getting started. Going to Antarctica had mostly been about me going there – exploring space to the contrary feels like it is something for humankind. It is both exciting and humbling to be a small part of this effort.

Perhaps the key thing I learned through my Antarctic stay was that I had really been able to go thanks to the support and encouragement of so many people who acted as mentors for me, from family to friends and colleagues, even astronauts – they all played a part. Thanks to them I dared believe that I could achieve things beyond what I previously considered possible. It was all these people’s belief in me that made me trust that I would be OK and that the journey was the right choice for me. They were right.

Whether it is to undertake a challenging Antarctic journey or to push the boundaries of humanity further into the Universe, it remains valid:

If you want to go faster, go alone, but if you want to go further, go together.

***

Told by: Beth Healey

Story development: Anders Jordahl

Discussion: one comment

Beth – thanks for sharing your experiences of your Antarctic Winter. The extreme isolation must have felt overwhelming at times, yet also juxtaposed with living in confined quarters with other people.

I rowed across the Atlantic (just 50 days) a few years ago, and your story reminded me of some similar experiences. I remember feeling utterly insignificant relative to the force of nature surrounding me. But also thrilled to see it and experience it.

Good luck with all the out-reach here back home.