ESA’s Pangaea geology training campaign chose a pearl in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean for planetary studies: the Canary Island of Lanzarote.

“Earth is the only real analogue we have at hand, and there are a lot of lunar lessons we can learn from this barren world dotted by volcanoes,” says Matteo Massironi Pangaea scientific coordinator and professor of structural and planetary geology.

The Canaries are a Spanish archipelago off the African coast. Their origin is linked to hot spot volcanism emerging above a slow-moving oceanic plate, with basalt as the bedrock of the islands. Here, lava flows compare to vast plains on the lunar maria – those large, basaltic areas on the Moon that appear dark to the naked eye from Earth.

“The snail’s pace of the tectonics in the Canaries relates to that of the Moon, where the mantle has been too cool for the plates to move actively. Nowadays it is a frozen world inside,” adds Matteo.

The remnants of magma eruptions from 300 years ago in Lanzarote helped the Pangaea crew to look for pristine and primitive samples from the Earth’s mantle.

Meanwhile, on the other end of the archipelago, rivers of lava keep emerging from La Palma for the third consecutive month. Matteo thinks this could be a great opportunity to study even fresher samples and the context around them.

“The amount of video and scientific data collected during La Palma’s eruption is so vast that we don’t need to infer the story behind. We are witnessing it!” he says.

Caves on the Moon

The current activity in La Palma is a recipe for future lava tubes. Lava tubes form when the surface of a lava stream cools and hardens, creating a tunnel through which hot lava flows, or when lava cracks its way through the underground. After the volcanic activity stops, the tunnels remain empty, leaving different-sized caves along its way.

Lava tubes also exist on the Moon, and could offer enough space, protection against cosmic radiation and stable temperatures for astronaut bases. In 2017, the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency detected in 2017 the existence of a skylight with a 50-metre wide opening and a depth of at least 50 metres on the Moon.

Lower gravity on the Moon – one sixth of that on Earth – explains their enormous dimensions and the fact that the majority of skylights have not collapsed.

“Since we can’t replicate lunar gravity on Earth, we came to one of the world’s largest volcanic caves – the Corona lava tube in Lanzarote,” explains Riccardo Pozzobon, Pangaea instructor in remote sensing and research fellow in planetary geology at the Italian National Institute of Astrophysics.

Although smaller than the lunar ones, the shape of the 8-km-long tube is similar to what we can find on the Moon.

Now that humans are set to travel to the Moon in this decade with NASA’s Artemis missions, Riccardo finds the similarities promising to start thinking about human settlements. “Lava tubes on the Moon could offer enough space and protection to host a human colony,” he says.

In the meantime, Pangaea’s next stop in 2022 is to find more lunar analogues in a Norwegian fjord, home to one of the best anorthosite samples on Earth – the same type of rock representative of the original lunar crust.

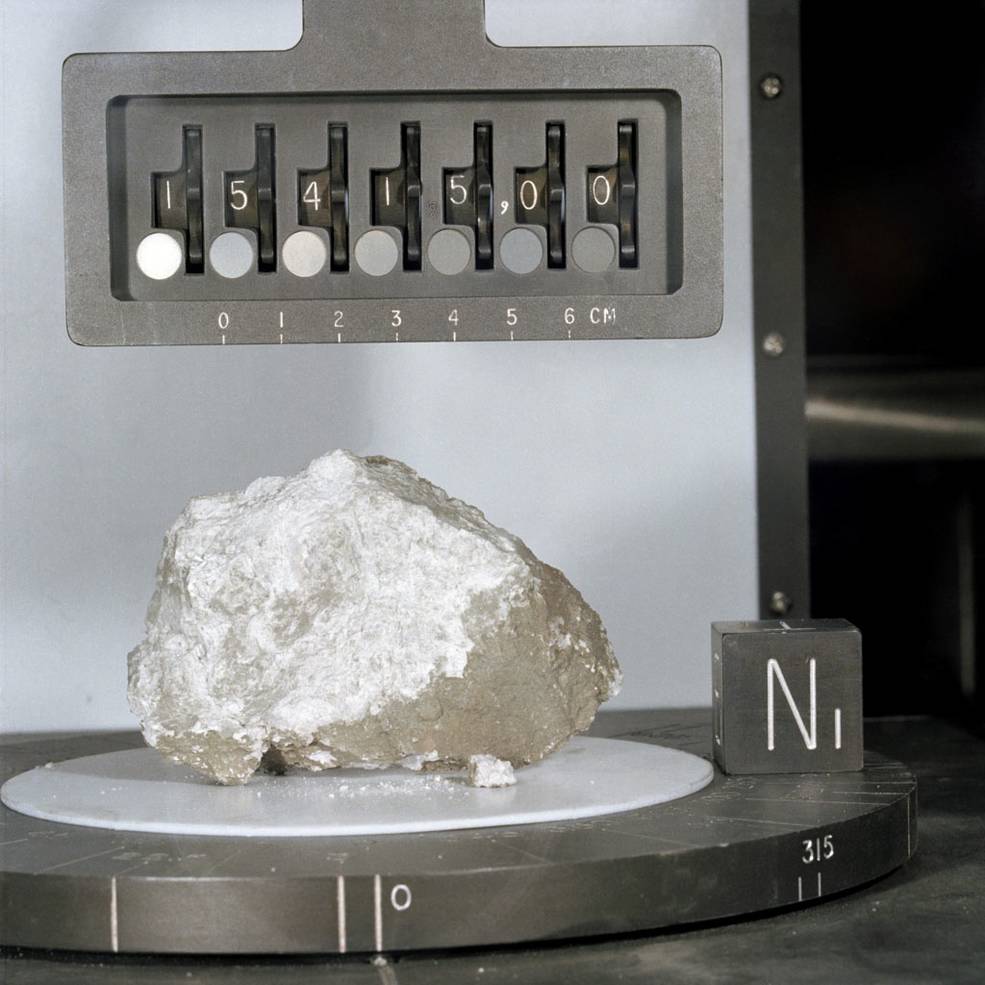

It was during the Apollo 15 mission that NASA astronauts Dave Scott and Jim Irwin collected the ‘Genesis Rock’, a 4-billion-year-old anorthosite and one of the most ancient rocks ever collected.

Their excitement of the discovery is evident in the transmission:

– Irwin: Oh, man!

– Scott: Oh, boy!

– Irwin: I got…

– Scott: Look at that.

– Irwin: Look at the glint!

– Scott: Aaah.

– Irwin: Almost see twinning in there!

– Scott: Guess what we just found. (Jim laughs with pleasure) Guess what we just found! I think we found what we came for.

– Irwin: Crystalline rock, huh?

– Scott: Yes, sir. You better believe it.

Let’s get ready to revive this geological excitement on the Moon.

Discussion: 3 comments

Merci d’avoir trouvé le lien en rapport authentique à l’alignement. Des volcans sur les islas Canarias.

¿Sabes qué animales viven allí?

Fascinating geology! We go back on the tracks of the Apollo astronauts indeed. Great initiative and great article Nadj!

Meanwhile in the SpaceResourcesChallenge.esa.int ESA and ESRIC we are looking for ways to let the robots do the first scouting/prospecting phases of lunar exploration. Exploring a lava tube is indeed a dream (of mine anyway) but it was a step too far to recreate in the analogue terrain we set up in Valkenburg (The Netherlands): teams were challenged to navigate some hurdles and analyse 6 rocks that we put into a simulated crater made of lava split. ANd we got support from the ESA Pangaea geologist as well!

Maybe one day the two initiative could come together!