Collisions in the universe are often an act of disruptive creation: small particles aggregate to larger ones, eventually forming asteroids and planets.

Impact craters, those bowl-shaped holes in the ground formed by an asteroid, are very common in the planets and moons of our Solar System. The cratered face of the Moon is a testimony to the frequency of asteroid strikes in our neighbourhood.

However, impact craters are a rarity on Earth. There are less than 200 on our planet, and only a few of them are well preserved and thoroughly researched.

ESA’s Pangaea geology course kicked off this week with a visit to the Ries crater, one of the best-preserved impact craters on Earth. About 15 million years ago, a giant asteroid of one kilometre in diameter hit Earth at 20 km per second releasing one trillion times the energy of the Hiroshima atomic bomb. The result is still visible in west Bavaria today: a 25km-crater with a depth of roughly 200 metres.

“At the Ries crater, Pangaea participants can find rocks similar to those found in craters of the Moon, mostly created by asteroids,” explains Professor Stefan Hölzl.

The finding of very special minerals – shocked quartz grains – in the 1960s gave evidence that an asteroid formed this crater. “This is what makes the Ries area an invaluable Moon-crater simulator on Earth,” he adds.

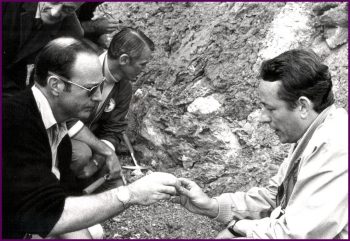

Apollo 14 field trip to Nördlingen Ries. From the left: Professor Wolf von Engelhardt, Dr. Ed Mitchell, Gene Cernan, and Dr. Stöffler. Credits: NASA

A place for astronauts

ESA astronaut Thomas Reiter and Roscosmos cosmonaut Sergei Kud-Sverchkov are not the first ones to participate in geological field training in this area.

In August 1970, four American astronauts from the Apollo 14 and 17 missions spent five days on a geology field trip in the crater. “It was just a few months before their flight to the Moon. At that time, the knowledge about lunar rocks and geological structures was modest,” explains Stefan.

The American crew got in touch with local geologists to understand more about lunar geology and to learn how to pick the best samples. “To this day, the visit of the Apollo astronauts is still very present,” he adds.

As they did, Pangaea’s participants went up the Nördlingen church tower to observe the impressive crater from above and see the entire town located within its boundaries. The city’s church of St. George is built with blocks of suevite — a rock melted by the asteroid impact.

The theory lessons are held at the research centre of the Ries Krater Museum, where participants are exposed to a wealth of documentation, samples and illustrations.

“Pangaea helps participants to better understand space by studying Earth. Our museum perfectly complements that approach – we try to show to our visitors the influence of space on Earth,” says Stefan.

Read the impressions from ESA astronaut Matthias Maurer during his visit to the Ries crater and the city’s church on this post from last year.

Discussion: no comments