We are in the middle of a 25-km wide impact crater in Nördlingen, Gemany, to look at impact rocks. With “we” I mean two ESA astronauts, Samantha Cristoforetti and Matthias Maurer, and several instructors from across Europe. What we are doing here is part of ESA’s astronaut training program called Pangaea.

Professor Harald Hiesinger with lunar geology map to teach lunar tectonics and volcanism. Credits: ESA–Elena Díaz

Since Wednesday, we have been talking constantly and passionately about geology and planetary science to geologically train our astronauts for flights to the Moon and beyond. Considering the numerous flight opportunities that arise from ESA’s international collaborations, it was a wise decision to get started with such a training, which has already attracted considerable interest from other space agencies.

The training follows the example set by the Apollo programme during which the astronauts of Apollo 14 and 17 were trained in the Ries crater in the summer of 1970. Finally, after all these years, new astronauts are back to learn about the Ries crater!

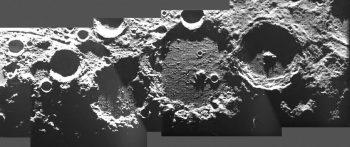

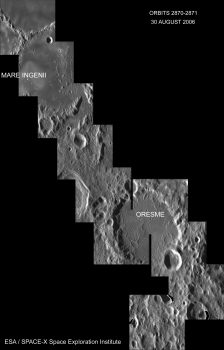

Lunar polar craters seen by ESA’s Smart-1 satellite. Credits: ESA/SMART-1/AMIE camera team/Space Exploration Institute, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO

For me, as one of the instructors, it is simply a pleasure to see the enormous interest of the astronauts in this training. Eager to learn, they ask hundreds of excellent questions and come up with even better suggestions for the future exploration of our Solar System – a very fruitful intellectual exchange of ideas and thoughts. In this respect, the Moon plays a special and unique role because it allows us to study 4.5 billion years of Solar System history and geological processes in their purest form. It is also our next neighbour that most easily can be reached with astronauts and can serve as a test bed for technology necessary for human spaceflight, for example to Mars. Thus, the Moon exemplifies how exploration and science can work hand in hand for the benefit of both disciplines. The Moon is not out of reach for us and it is the next logical step forward!

Impacts litter the surface of the Moon from sizes as small as a millimetre all the way to the largest basin in the Solar System, the 2300-km diameter South Pole-Aitken basin on the lunar far side. This is why we are here in Nördlingen.

The Nördlinger Ries impact crater was formed about 15 million years ago and is one of the best-preserved craters on Earth. As such, it is an invaluable source of information to better understand the cratering process. A solid understanding of this process is important for astronauts that might walk across the surface of the Moon. Today is the day that we are looking at impact rocks across Nördlinger Ries in detail, including the suevite, the bunte breccia, the crystalline breccia, and some impact melt.

All dressed in green T-shirts and jackets, we are not sure if we look more like Martians than lunatics when we climb the tower of the St. George’s church. After getting a “remote sensing” perspective from the top of the tower and a first glimpse of the sheer size of the crater and its general morphology, we head out to Wengenhausen to look at the crystalline breccia. Originally located several hundreds of meters below the surface, these rocks were heavily fragmented and brought to the surface by the impact.

We get a first idea of the forces that were unleashed during the formation of the Nördlinger Ries and are stunned. As a bonus, we can also see fossil-rich sediments, which were deposited in a lake that once occupied the crater. This makes the Ries crater also interesting for Mars where numerous presumed crater-lakes have been identified. Our next stop is the famous outcrop in Aumühle were we can study the enigmatic relationship between the suevite and the bunte breccia before we move on to Polsingen to see the only outcrop of impact melt still accessible in the Nördlinger Ries.

In the very impressive quarry of Gundelsheim, we discuss the emplacement of the bunte breccia, which left spectacular striation marks on top of some Jurassic limestone. Finally we stop at the Riegelberg, one of the so-called mega blocks that were moved and shattered during the impact process.

Exercises throughout the day were waiting for the astronauts, including describing rocks, identifying minerals, sketching outcrops, and developing their own models of the Ries crater geology. As instructors, we help them by pointing out the important observations that can be made rather than just “telling them the story”. No, they have to figure it out all by themselves – one piece of the puzzle after another. A very challenging task but also very instructional. They loved it and are good at it! I cannot wait for another training session with the astronauts and more field work next year.

In the meantime I will think more about research that we could do in Matthias Maurer’s unique “European Surface Operations Laboratory” that will allow us to test instruments and procedures in a lunar analogue environment. The Moon is waiting for us. Let’s start the count down!

Harald Hiesinger

Discussion: no comments