Post from Rudy Castorina (Ocean Media Lab)

Marking a historic milestone in the voyage, the ship’s Norwegian flag was flown over the Porcupine Abyssal Plain, known as PAP – a sentinel of the Atlantic and site of one of the world’s longest-running deep-ocean monitoring programmes. At this iconic location, the training course students stepped into a living legacy of ocean data and scientific discovery.

The day begins with a coordination meeting led by the station manager. Students gather around to review satellite data, safety procedures and roles for the upcoming CTD deployment at the Porcupine Abyssal Plain. (Ocean Media Lab)

The morning began on deck with the usual station coordination meeting. Watch teams gathered around the station manager to finalise plans, review safety protocols and synchronise the day’s operations.

Behind the calm of the briefing lay hours of preparation as the choice of this station wasn’t random – PAP is a specific location.

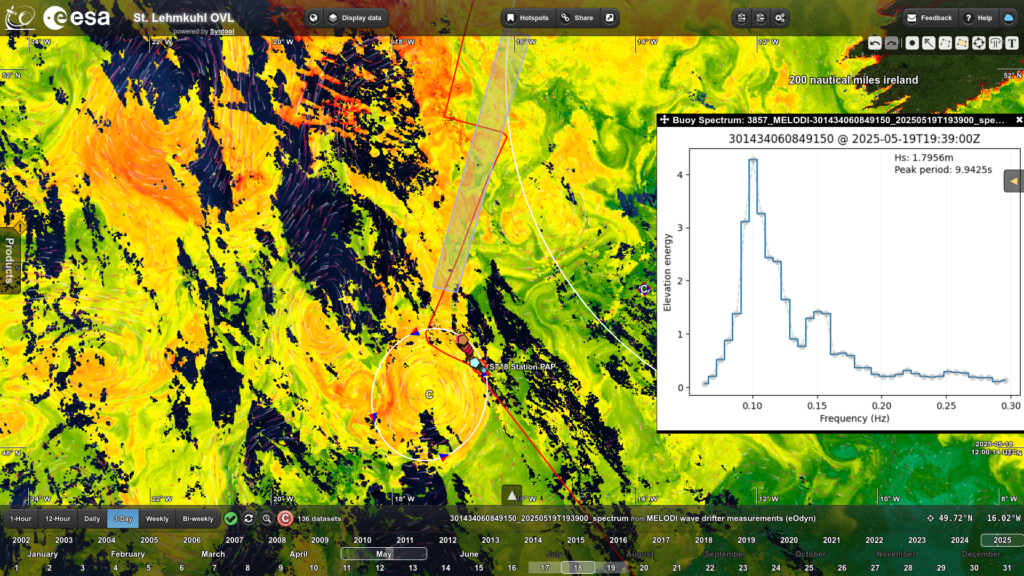

A large oceanic cyclone (outlined in white), detected by satellite altimetry over the Porcupine Abyssal Plain, is shown alongside chlorophyll concentration data from Sentinel-3. Nutrient-rich waters upwelled by the cyclone fuel surface photosynthesis, leading to elevated chlorophyll levels that are carried by ocean surface jets and eddies. MELODI wave drifters (wave spectrum shown) and student-built drifters were deployed to validate satellite observations of upper ocean dynamics. The ship’s track is marked in red. (Dr Fabrice Collard from Ocean Data Lab)

Sentinel-3 satellite data – particularly ocean colour and sea-surface height – was used to understand the condition of the ocean at the time we deployed the oceanographic instruments, bringing realtime Earth observation into action.

The station manager oversees the CTD deployment process from the upper deck, ensuring that all procedures are followed safely and smoothly as students coordinate the operation below. (Ocean Media Lab)

Deck & watch leader monitors the descent of the CTD rosette into the deep. PAP is one of the world’s longest-running deep ocean monitoring stations, and now the Ocean Training Course students are part of its data legacy. (Ocean Media Lab)

The conductivity-temperature-depth (CTD) rosette was dropped overboard under clear skies, returning with water column data that students quickly turned into samples, numbers and learning moments.

Mark Drinkwater, who heads ESA’s Mission Science Division, and student Unyime Umoh work together to extract water from the rosette’s sampling bottles. The data collected will be matched to satellite readings, completing the satellite-to-sea cycle in real time. (Ocean Media Lab)

Alongside, the DIY ‘Open CTD’, engineered and built by students while aboard the ship, was deployed again for testing, a symbol of their growing capacity as both scientists and engineering innovators.

This type of problem solving and innovative solution finding is exactly what the European Space Agency uses every day when developing Earth observing satellites.

Student Molly Alexandra Phillips prepares water samples for filtration and analysis. Each drop of seawater becomes a reference data point to validate data captured from space. (Ocean Media Lab)

Back on deck, the pace never slowed. Students collected water into sample jars, prepared filtration kits and recorded their findings with precision. Some pored over laptops cross-referencing satellite datasets, while others took their turn at the helm or braced ropes during routine sail handling.

Student, Marie-Christin Juhl, collects water from the CTD bottles, readying it for nutrient and biological analysis. (Ocean Media Lab)

Between deployments, students discuss chlorophyll concentration patterns observed in Sentinel-3 data and how they align with the physical measurements collected at sea. From left to right: João Vitor Langor Bueno, Sejal Pramlall & Lou Andrès. (Ocean Media Lab)

Students, Eva Chamorro, Salma Sheini & Lou Andrès coordinate the launch of a fine-mesh plankton net, another layer of biological data collection that complements satellite indicators of productivity. (Ocean Media Lab)

Fine-tuning the DIY OPEN CTD before its deployment. Built on board, it symbolises the growing technical confidence and ingenuity of the OTC participants. (Ocean Media Lab)

Aboard the Statsraad Lehmkuhl, science doesn’t stop for sailing – life at sea and learning move in unison. This is exactly what makes this ship such a unique and powerful classroom for ocean science.

Throughout the day, the physical rhythm of seamanship continued: helms rotated, lines hauled and sails adjusted – training the body alongside the scientific Earth observation mind. Later, under the soft light of evening, the deck transformed once again, this time into a lecture space.

Student Walter Okinyi Ogutu takes the helm as part of the rotating watch schedule, steering through deep Atlantic waters. (Ocean Media Lab)

Pulling together, students and crew members adjust rigging lines. Just as science requires collaboration, so too does navigating a tall ship through shifting winds and waves. We can see Astronaut Pablo Àlvarez blending in with the students. (Ocean Media Lab)

ESA astronaut Pablo Álvarez, who had spent the day with the students during operations, gathered the crew below deck for a talk. In a powerful moment of connection, he shared his personal path from being a student of engineering to becoming an astronaut. He reflected on perseverance, international teamwork, and the importance of scientific curiosity.

ESA astronaut Pablo Álvarez offers a personal account of his journey to space. In this special onboard lecture, he draws powerful parallels between life aboard the International Space Station and life at sea, reminding students that exploration, whether oceanic or in space, begins with curiosity and courage. (Ocean Media Lab)

His presence reminded students that exploration comes in many forms, and that their work at sea connects directly to humanity’s broader quest to understand our planet. During the ESA Ocean Training Course, we often talk of tall ships and spaceships, discussing the similarities in living, eating, working and performing scientific experiments in a remote location.

This dual rhythm of science and sail, satellite and salt spray, is exactly what makes the voyage unique. It’s not just about learning about data; it’s about embodying the responsibilities of an ocean ambassador.

At PAP, the past met the future. Legacy data merged with new measurements. And the ocean, once again, reminded us that its story is being written by those who listen to both the satellites above and the waves below.

Discussion: no comments