During one of his lectures William Thomson said, “When you can measure what you are speaking about, and express it in numbers, you know something about it; but when you cannot measure it, when you cannot express it in numbers, your knowledge is of a meagre and unsatisfactory kind.”

This quote is deeply inspiring if you think about the ASKOS Aeolus experimental campaign. In Cape Verde this summer, researchers from a range of institutes joined forces to observe the Earth, take atmospheric measurements and try to understand how the weather works.

From severe downpours and burst tyres to terrifying creepy crawlies, we had quite a few adventures in the process.

JATAC Campaign: collaboration of giants

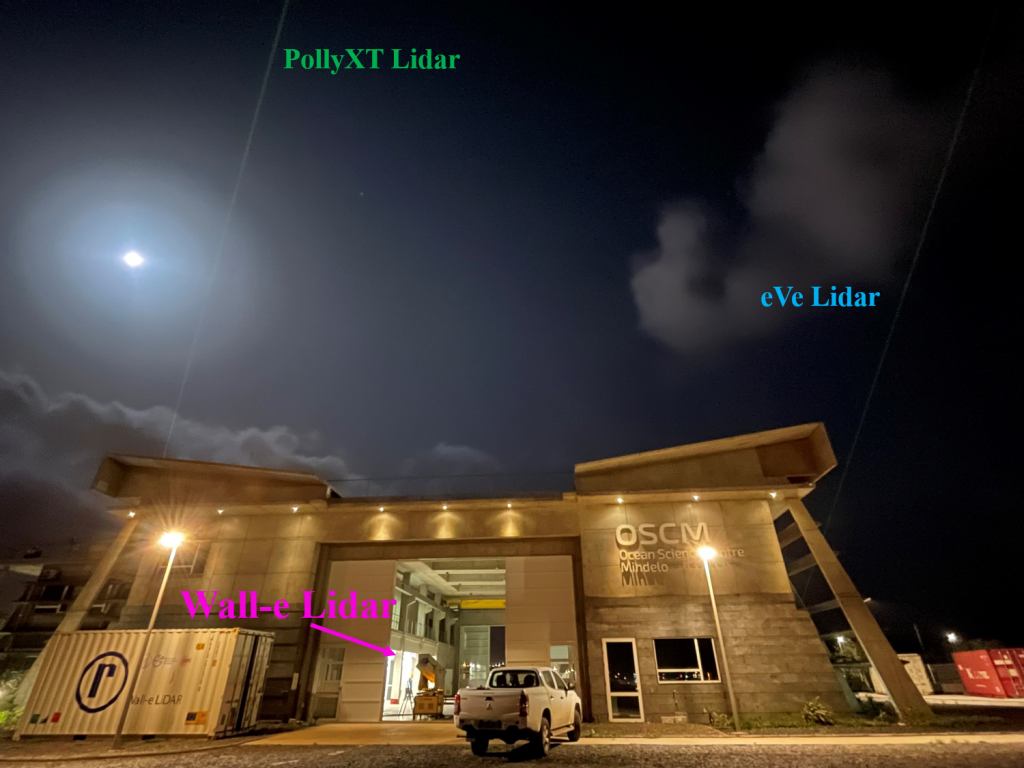

During 6-23 September 2022, scientists from National Observatory of Athens (NOA) and Leibniz Institute for Tropospheric Research (TROPOS) gathered at the Ocean Science Centre of Mindelo (OSCM) on São Vicente island of Cabo Verde, to complete the ground-based operations of the Joint Aeolus Tropical Atlantic Campaign (JATAC) organised and led by ESA’s Aeolus mission.

Ocean Science Centre of Mindelo (OSCM) on São Vicente island of Cabo Verde (Credits: V. Spanakis, P. Paschou)

The primary purpose of the campaign is to calibrate and validate the aerosol and wind products of the Aeolus satellite, ESA’s unique doppler wind lidar mission. The ground-based component of the JATAC campaign is called ASKOS, named after the Greek word for Aeolus’ legendary bag that contained all the storm-winds.

As you can imagine it was quite an experience to live and enjoy in the third year of my PhD studentship.

It’s not all rosy in the garden of an experimental campaign

On Monday 5 September, our trip to Cabo Verde began and the only restriction was that my excitement could not fit in the luggage.

Despite the intensive preparation for the campaign, there will always be issues when it comes to weather, starting from day one. We arrived at Mindelo with an easy connection through Lisbon, Portugal, but the moment we stepped onto the soil of Cabo Verde, an unpleasant surprise welcomed us.

Aerial view over Mindelo, Cabo Verde (Credits: I. Tsikoudi)

A severe rain event took place before our arrival, so when the plane landed we faced flooded roads, closed shops, foggy skies and muddy waters. We intended to understand the weather but the weather got us first!

Floodings in Mindelo, São Vincente (Credits: I. Tsikoudi)

This situation would also create several problems with our measurements and access to OSCM. And this was just the beginning…

After a few days Vasilis Spanakis (NOA) and Dimitra Kouklaki (NOA) ended up in the hospital with food-poisoning which they fortunately overcame. Not only that, we also had nine days delay for Dimitra’s luggage to arrive in São Vicente and our car’s tyre burst. You might say things don’t always go according to plan!

The ground-based measurement site

Several instruments were installed at the main roof of OSCM in June 2021 at the beginning of the campaign.

Instruments on OSCM roof (Credits: V. Spanakis, P. Paschou)

Our first job was to restart the instruments after the severe rain event, ‘dust them down’ and maintain their continuous operation. Two of the leading players were the eVe Lidar and Wall-e Lidar, operated by Peristera Paschou (NOA) and Spyros Metallinos (NOA).

Unfortunately TROPOS’ PollyXT Lidar suffered from a broken chiller and the replacement was stuck at the airport. But obstacles exist to be dismantled and by 13 September, Athena Floutsi (TROPOS) and Dimitri Trapon (TROPOS) had PollyXT ready to face all measuring challenges.

Athena and Dimitri with PollyXT Lidar (Credits: I. Tsikoudi)

Vasilis Spanakis even managed to fit the 3 lidars in one picture! Well, Wall-e doesn’t have a visible beam like PollyXT and eVe Lidar, but it stands proudly at the front of OSCM.

The three lidars: PollyXT, eVe and Wall-e (Credits: V. Spanakis)

Coordinated action between two islands: São Vicente and Sal

In addition to our ground based measurements in Mindelo, University of Nova Gorica scientist Griša Močnik and pilot Matevž Lenarčič performed daily flights with the Aerospool Advantic WT-10 to support the main objectives of CAVA-AW. The size of the aircraft was relatively small, but the measurements provided were of major importance.

Griša Močnik and Matevž Lenarčič with Aerospool Advantic WT-10 at Cesária Évora Airport (Credits: E. Marinou)

At the same time, in a nearby island of Cabo Verde, Sal, NASA scientists were conducting the CPEX-CV experiment with airborne measurements onboard the 42m DC8 aircraft. Every day we were communicating about instrument performance, the planned DC8 track, and discussing the weather and dust forecast above our site, in order to organise the measurements we would perform.

Ready to join the DC8 flight at Sal (Credits: E. Marinou)

Dr Eleni Marinou from NOA was our campaign organiser and the essential connecting link between the two islands, ensuring efficient and close coordination between all partners. She, along with Thorsten Fehr (Head of Atmospheric Section at ESA), visited NASA operations and after learning all the security rules, had the chance to join a DC8 flight and captured what dust looks like from above.

The DC8 was full of instruments, operators, scientists and computers with colourful graphs. The orbit and the time of each flight would be determined by cloud presence and dust transport.

Reading instruments on DC8 (Credits: E. Marinou)

Nighthawks exploring the weather

Nighttime measurements were a big piece in our puzzle. The night shifts were split so that all team members would have the experience to spend a night (or two) at OSCM, operating the Wall-e Lidar also for the objectives of the D-TECT project, supported by European Research Council (ERC). Dr Alexandra Tsekeri (NOA), who was based in Greece, shared the same level of sleeplessness with us, in order to supervise Wall-e’s measurements. After almost 48 hours of continuous measurements, we finally managed to see that dust particles can be oriented (a major goal of our research)! One thing’s for sure: tiredness was not a restraining factor for our excitement.

Occasionally creepy crawlies would keep us company (after initially terrifying us with huge, multi-limbed shadows on the wall), like the giant crab that was staring with curiosity at our helium tanks. At first our meeting was pretty scary, but after a while we chilled peacefully all together, admiring the green beams in the sky. Many cats also showed interest in our work. After all, when you are a cat you have to know if it is going to rain.

(Credits: I. Tsikoudi)

We did some science during the daytime too!

A radiosonde is a big weather balloon, filled with helium, which can reach up to 20 km high and carries sensors which measure crucial meteorological parameters, like temperature and relative humidity. It is actually a precious type of measurement technique for atmospheric physics, because it is very accurate and can verify the data collected from the other instruments installed on the ground or on a plane. In Cabo Verde, launching a radiosonde was one of the most interesting and fun events. The balloon’s liberation in the limitless sky was one of the best moments to capture!

Releasing a radiosonde (Credits: P. Paschou, E. Marinou, V. Spanakis)

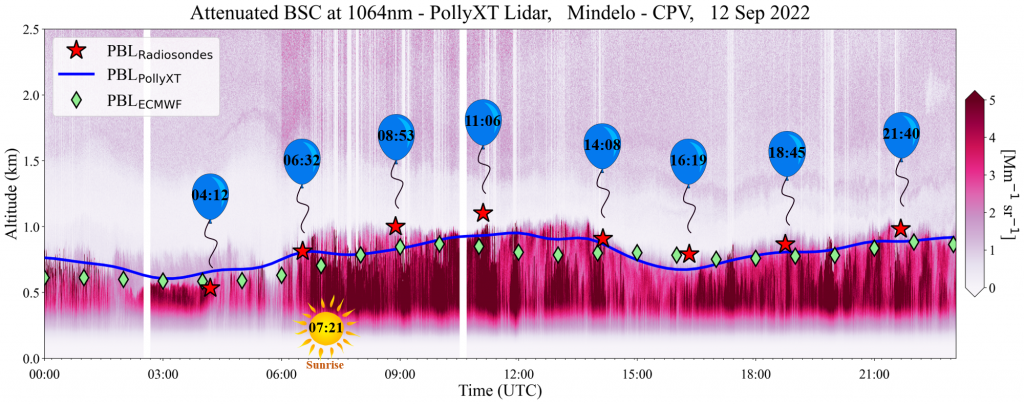

The synergistic use of the instruments allowed the support of many scientific objectives, among which was also my PhD topic: the study of the Planetary Boundary Layer (PBL), the layer in which we live and breathe. This means that we could perform some tailored measurements, with the highlight being that Ι was able to release 9 radiosondes in 24 hours, with the help of the rest of the team. The measurements we collected that day will give us some golden information about PBL structure and dynamics.

Some preliminary PBL results (Credits: I. Tsikoudi)

We also had the chance to meet Professor Nilton Evora from Universidade Federal de São Paulo, with whom we discussed the radiosondes and the electric sensors Vasilis Spanakis and Vasiliki Daskalopoulou (NOA) had constructed.

The review

The difficulties were for sure multiple and there were forces we couldn’t overcome, but at the end of the day science is fun and charming. Teamwork and motivation are the keys to withstand any problems that for sure will arise. What I also realised in this field campaign, is that free time and rest is more than necessary to enjoy the demanding working routine. After a long day, we would drink cold Grogue (a traditional beverage of Cabo Verde) at the central square of São Vicente, or bond with the locals by playing football.

ASKOS ground-based team at the central Square of Mindelo (Credits: I. Tsikoudi)

The best moment was the sunset.

And here comes science again: usually a sunset is of orange-red colour, but when there are dust particles in the atmosphere, the sunset is yellow to whitish and dull. Even though a yellow sunset is not as impressive as a flaming one, it is pretty awesome that we can explain it and practically measure the dust concentration that indirectly ‘steals’ the red charm from the sunset.

Yellow to whitish sunset from OSCM (Credits: I. Tsikoudi)

In the ASKOS Campaign, we had everything. Interesting science, ups and downs, nighttime visitors and yellow sunsets. The next step is to dive deep into the data and read the stories the numbers will recount!

Post from: Ioanna Tsikoudi, PhD student at the National Observatory of Athens

Editor’s note: Ioanna Tsikoudi is a PhD student at NOA, whose travel was funded by COST as a Short Term Scientific Mission (STSM). ASKOS campaign was funded from ESA’s ASKOS project and the D-TECT ERC project, and supported by ACTRIS.

Discussion: no comments