ESA’s cloud and aerosol mission, EarthCARE, is in its commissioning phase after a successful launch in May 2024.

Now its four instruments have been turned on -the cloud radar, broadband radiometer, multispectral imager and atmospheric lidar– it’s time for the all-important calibration and validation.

That’s being carried out by a huge international network of scientists working on a campaign known as ORCESTRA.

From Cape Verde to Barbados, it involves multiple aircraft, drones, balloons and a huge research ship, all of them working in coordination to measure the clouds and aerosols in Earth’s atmosphere over the tropical Atlantic. And, importantly, right underneath EarthCARE as it passes overhead.

One of those scientists is Bernhard Mayer, who is chair of experimental meteorology at the Meteorological Institute Munich at LMU. He also happens to be a fantastic photographer and delivered his personal insights, and pictures, into the campaign via LMU’s “takeover” Instagram account.

Here’s a week in the life of a validation campaign, through images of the team and the equipment they are flying to make sure EarthCARE data is tip top.

Bernhard Mayer, pictured here preparing for a flight. (Meteorological Institute Munich, LMU-Bernhard Mayer)

Introducing HALO

This week we would like to invite you to accompany us to Sal in Cape Verde for cloud research.

“We” — that is Lea Volkmer, Veronika Pörtge, and me (Bernhard Mayer).

Why do we all have a yellow jacket and headphones? It is an aircraft measurement campaign with the DLR research aircraft HALO and several other aircraft, ships, and measuring stations.

The team gets ready to board the HALO for the first day of flights (Meteorological Institute Munich, LMU-Bernhard Mayer)

HALO is a converted Gulfstream 550 that has space for almost three tonnes of measuring devices.

One of them is our spectral imager, “specMACS”, which has six highly specialised cameras that precisely probe clouds from 10 km away.

For the photography fans: four of the cameras each save five RAW images per second. You need a lot of SD cards for this… If everything works out, we will end up 10 terabytes of data richer after each flight!

Lea, pictured below, has to spend nine hours on the plane, making sure that all six cameras measure properly, none of the computers choke, and the windows don’t freeze over!

Lea, on the steps of the HALO aircraft. (Meteorological Institute Munich, LMU-Bernhard Mayer)

Chasing thunderstorms

We have found the first thunderstorm!

The island Sal has very little precipitation, but if you fly into the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) you will find thunderstorms.

HALO, the French SAFIRE, and the EarthCARE satellite met at exactly the same coordinates at exactly the same time along the way. You might find it a bit nerdy to be excited about something like that, but you must know that this is the result of decades of planning.

EarthCARE was selected by ESA in 2001 and barely 23 years later was launched into orbit by a Falcon 9, where it has been since May 2024. Yesterday, all EarthCARE instruments were up and running for the first time, on the first day of a validation campaign that has been four years in the making.

Precision timing, you could say. And EarthCARE is one of the most interesting missions in climate and cloud research right now!

HALO has roughly the same instruments on board as EarthCARE, and every two to three days we try to fly exactly below EarthCARE to “validate” the satellite instruments, i.e. to check whether the devices are measuring correctly.

On the HALO, the team checks in on the vital measurements. (Meteorological Institute Munich, LMU-Bernhard Mayer)

Ground day

Today was “ground day”. While Veronika and Lea improved the software and ensured that the aircraft windows were squeaky clean, I took care of the flight plan for Sunday.

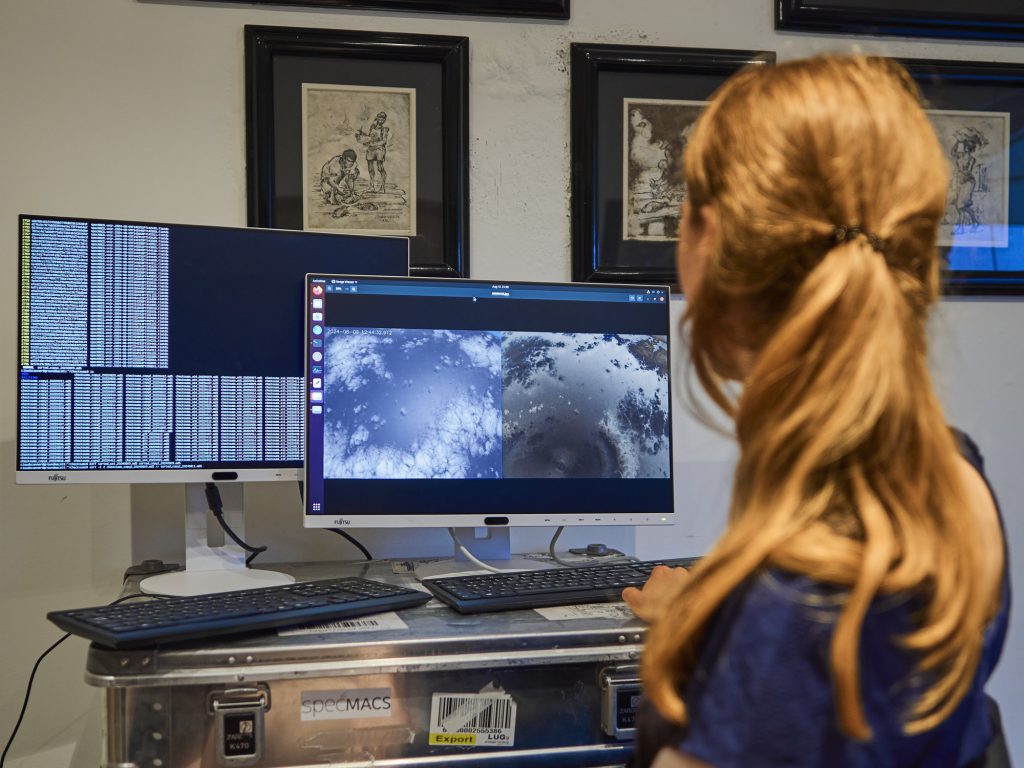

We have now also set up the servers for data analysis. On the screen you can see what we are looking for: the “cloudbow” and the “glory”.

Veronika at the computer screen searching for cloudbows and glories. (Meteorological Institute Munich, LMU-Bernhard Mayer)

The cloudbow is basically a rainbow, except that it is produced by smaller droplets. It is not as colourful or as visible as a rainbow, but with the help of our polarisation-dependent camera we can make it visible.

You can also see the cloudbow with polarised sunglasses or a polarising filter for the camera.

You have probably seen the glory, also known as the Brocken spectre, if you have ever been on a mountain and looked at the clouds below you.

Why do we measure cloudbows and glories? From the shape and size of the rings, we can very precisely determine how large the droplets in the cloud are. The size of the droplets determines how much solar radiation the cloud reflects and thus how much the cloud cools Earth.

It is also crucial for the lifespan of the cloud and the formation of rain. The number and size of the droplets is influenced by the number of particles (aerosols) present in the atmosphere, because clouds form when water condenses on particles (known as condensation nuclei).

Our specMACS device allows us to measure the diameter of droplets that are only a hundredth of a millimeter in size from 10 km away, using cloudbows and glories.

We certainly deserved a proper home-cooked dinner after all those insights.

Lea, Bernhard, and Veronika sit down for a well-earned, home-cooked dinner after a hard day’s work. (Meteorological Institute Munich, LMU-Bernhard Mayer)

A well-earned day off

Everyone who has anything to do with HALO has to take a 36-hour break once a week.

During our break we explored the island. There aren’t that many highlights because the island isn’t very big and consists mostly of sand.

The “blue eye” was warmly recommended to us. This is a natural cavern filled with water. When the light shines in from above (which it does at this time of year from 11 am to 1 pm), you can see the water glowing beautifully blue.

The natural cavern known as the “blue eye”. (Meteorological Institute Munich, LMU-Bernhard Mayer)

More flight planning

Before we can take to the skies again from the shimmering heat of Sal, a lot of planning is required on the ground. Tomorrow is “my” flight — I’m on board as mission PI, responsible for planning and executing the measurement flight.

The best ideas come from napkins during the coffee break!

Of course, there’s a little more to it than a napkin.

How much do you know about tropical meteorology? The wind tends to blow south of the intertropical convergence zone from the south and north of the convergence zone from the north. Wind direction and speed are influenced by the Earth’s rotation and monsoon circulation. The convergence zone is where the winds from the north and south flow together — hence the name.

The converging air moves upwards and this creates the characteristic high cloud cover, which can extend up to 15 km in the tropics. We want to orbit the northern and southern edges and the middle of the convergence zone, and we also need to fly under EarthCARE.

You can then see this combined on the flight plan. As a special treat, tomorrow we’ll try to spontaneously fly around a thunderstorm if we find something suitable. Some very high clouds are forecast that we may not be able to get over. It will be very, very exciting.

The HALO poised to fly towards the thunderstorms of the intertropical convergence zone. (Meteorological Institute Munich, LMU-Bernhard Mayer)

A fantastic flying day

Today was a fantastic flying day!

As planned, we travelled for nine hours to investigate the intertropical convergence zone. Today it was particularly pronounced and where we had planned our circles there was a huge system of several thunderstorm cells.

With HALO we barely got over it at flight level 450 (13,700 m). Remember that we want to remotely explore the clouds from above and not fly into them. You can imagine that it was quite turbulent.

We were also able to realise our special request to fly around a thunderstorm.

On board the HALO aircraft. (Meteorological Institute Munich, LMU-Bernhard Mayer)

We are richer by many impressions and ten terabytes of data, which will be evaluated in the next few months.

I hope we were able to show you how exciting current cloud, weather and climate research can be.

If you would like to know more, please get in touch or have a look at my Instagram page.

Thank you to Bernhard Mayer for this blog, which was based on his account shared on LMU’s “takeover” account on Instagram. For more on EarthCARE, ESA’s cloud and aerosol mission, visit the EarthCARE homepage.

Discussion: one comment

So important to be able to monitor and understand how we change the atmosphere of our planet. And websites like this and others on EO-missions are extremely important to raise public awareness. Great job!