Late last year, scientists teamed up in Antarctica for an important field campaign. This mainly involved under flying ESA’s CryoSat satellite and NASA’s ICESat-2 satellite to take simultaneous measurements of sea ice. The campaign served as an essential inter-satellite calibration step and paves the way for the future use of the separate satellite measurement records.

Here we post ESA’s Isobel Lawrence’s personal account of this extraordinary scientific campaign, which gives us an impression of what it’s really like for those taking part – motion sickness and all!

5 December: welcome to Rothera

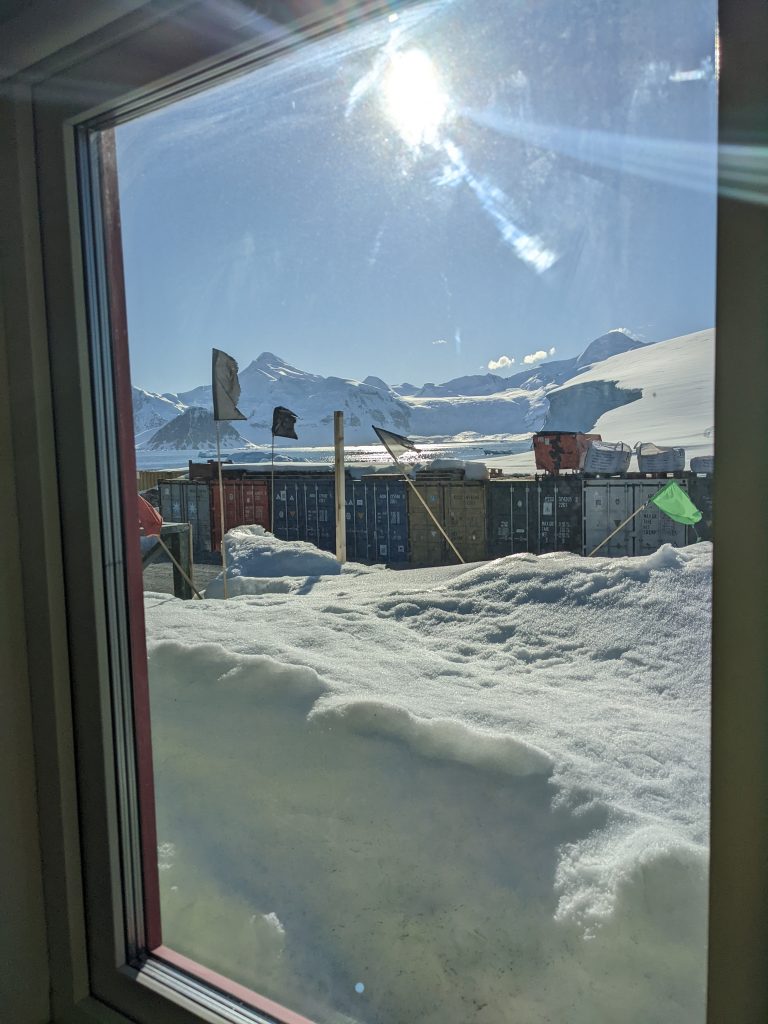

Looking east towards the peninsula. (credits: ESA–I. Lawrence)

After four days in Punta Arenas (and having exhausted the menu at La Marmita), we have finally arrived at Rothera. We were blessed with a beautiful, sunny day so the scenery as we landed was spectacular. We’re greeted as we disembark by the station leader, “Welcome to Rothera, Welcome to Antarctica!” and I’m struck by how it’s not as cold as I was expecting.

Disembarking the Dash-7. (credits: ESA–I. Lawrence)

After some settling in finding our rooms and unpacking, we head back to the main building for training. The site is divided by the runway, and if you’re working down in the hangar, like we are, you have to cross it frequently. With five planes routinely operating out of the base, it’s surprisingly active. Between that, the building work that’s going on here at the moment, and of course the harsh polar environment, there are a lot of safety precautions to be briefed on. An unpleasant photo of someone with burnt corneas is enough to convince me to wear my sunglasses and apply sun cream liberally.

My view. (credits: ESA–I. Lawrence)

After training we head for dinner. All meals (breakfast, smoko (like brunch), lunch, afternoon tea and dinner) take place in the dining room. There’s room for about a hundred people, and a ping pong table.

6 December: set-up begins

Weather delays and some aircraft repairs means we have arrived in Rothera behind schedule and are a bit behind rigging the plane. The Dash-7, which brought about 16 of us to Rothera from Punta Arenas needs converting from a passenger aircraft into our survey plane for the next ten days. This means removing all the seats and installing our instruments. This campaign is the first time that the Dash survey hatch (basically a big hole in the belly of the plane) is being used, and with nine separate instruments to install there is a lot to do before we’re ready to go.

Gaëlle, Sebastian and Carl unpacking instruments. (credits: ESA–I. Lawrence)

Meanwhile, the ground team (Andy and Ines) are busy outside the hangar constructing their ‘corner reflectors’. These are metal plates mounted on ~3.5-metre-high tripods, which have been custom-designed for this campaign and will help calibrate the radars we’re installing on the plane. They will be erected up on Fuchs Ice Piedmont where the team will also take ice cores to assess the snow and firn conditions. As the first one gets built there is some back and forth to the Twin Otter, the aircraft that will take them up to the piedmont, to check it fits through the door. The more that can be constructed at base, the less fiddling around with tiny screws and bolts with cold fingers and in deep snow out in the field.

Andy and Inès check if the top of the corner reflector will fit in the Twin Otter. (credits: ESA–I. Lawrence)

The team! From left to right: Carl Robinson (BAS), Sebastian Simonsen (DTU), Andrew Shepherd (Univ. of Leeds*), Inès Otosaka (Univ. of. Leeds), Isobel Lawrence (ESA), Gaëlle Veyssière (BAS) * now at University of Northumbria. (credits: ESA–I. Lawrence)

7 December: flight planning and penguins

With today bringing more sun and blue skies, Andy and Inès head off early in the Twin Otter to install the corner reflectors. I leave Carl, Gaëlle and Sebastian to continue with the Dash-7 installation and head to the office to plan our first sea-ice survey flight over the Weddell Sea.

Looking north up the runway and across to the hangar. (credits: ESA–I. Lawrence)

The objective with the sea-ice flights is to fly along satellite ground tracks, ideally at the same time that the satellite is passing overhead. The orbits of the satellites are known ahead of time, so a decent amount of planning was done before we arrived. However, now that we’re here, there are other things to consider too; namely, the weather and the sea ice conditions. We had planned, for example, to survey sea ice in the Bellingshausen Sea during this campaign. But this year, for the first time since satellite records began, there is no sea ice in the Bellingshausen within range of Rothera. So, we quickly had to abandon that plan and focus all our attention on the Weddell.

Andy and Inès return from the field having successfully put up all four corner reflectors, and the Dash installation is going well, so after dinner we do our first walk around The Point. Rothera is on a small promontory; it feels almost like an island that is attached to Adelaide Island by the runway. You can walk (or run!) the perimeter of this promontory in about 40 minutes, and with a lot of construction going on at base, it’s a lovely opportunity to feel a bit more in the wilderness. We spot our first penguins (chinstrap) and some seals who are blissfully unfazed by our presence.

9 December: airborne

Before making the long journey across the peninsula to the Weddell Sea, it’s essential to know that all the instruments are working correctly, so we head out this morning for a test flight. The plan is to leave Rothera and find some sea ice. This will give an indication of whether the radiometers, which are measuring the albedo (brightness) of the surface, are working. I am fortunate enough to sit in the jump seat – the third seat in the cockpit – for our maiden survey flight; a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to experience take-off and landing from the front of the plane. It’s a good remedy for the anxious flyer.

View from the jump seat when landing. (credits: ESA–I. Lawrence)

Carl, Seb and Gaëlle monitoring the instruments. (credits: ESA–I. Lawrence)

Shortly after setting out, we realise that one of the instruments (the Ka-band radar) isn’t giving us a signal, so we cut our journey short and return to Rothera to try and fix it. Back in the hangar, Sebastian and Carl manage to diagnose the problem – a dodgy cable. With that replaced, the race is on to refuel and leave to hit our first satellite overpass. CryoSat will traverse south to north across the Weddell Sea at 17:20 this afternoon. With half of the satellite overpasses in the late afternoon and the rest early the following morning, we will be taking it in turns to be in the plane, and I sit this one out. At about 23:00, after dinner and a few rounds of pool, I head to the hangar to meet the crew off the plane. After an eight-hour round-trip they are a little dishevelled but report that all went well and that the Ka-band radar is working.

10 December: Fuchs Piedmont

The local weather is going to be good all day, so we decide to take the Dash up to Fuchs Piedmont and overfly the corner reflectors that Andy and Inès put up a few days ago. It only takes about 15 minutes to get there. Initially I think that what I’m looking at (a perfectly flat, smooth white surface, bordered by mountains on one side) is low cloud sitting in a valley. Then I realise that it’s snow, totally homogenous from our 300-metre survey altitude. We fly back and forth along long parallel lines. The idea, as well as overflying the corner reflectors, is to survey as much of the area as possible.

View from the cockpit over Fuchs Piedmont. (credits: ESA–I. Lawrence)

The instruments on board will give us information about the surface, so the more ground we cover, the more information we have. The parallel tracks have been pre-programmed into the plane’s navigation system, so all the pilots need to do is turn the plane around at the end of one line and direct it to the next, avoiding the mountains and occasionally disabling the loud warning that tells us we’re getting too close to them. We can see on the navigation system that one of the corner reflectors is not far away, out to our left. I look out the window but see nothing.

Inside the Dash-7. (credits: ESA–I. Lawrence)

On the next traverse we’re a little closer, and this time I see the tracks made by the Twin Otter, and the black flags erected by the ground team to mark the site. I am taken aback by how tiny it is! No wonder I couldn’t see it before, I was looking for something much larger. But when you’re looking down at a vast white blanket with no point of reference, it’s impossible to get a sense of scale. Some way into the flight after a lot of to-ing and fro-ing I start to feel nauseous – motion sickness on a plane is a first for me – and I spend the remainder of the journey looking out of the cockpit window at the horizon.

Trace of the Twin Otter landing site from the cockpit window. (credits: ESA–I. Lawrence)

11 December: pancake ice

I wake up early and can’t get back to sleep so I head out for a jog around the runway. Green ‘open’ signs indicate that it’s safe to do so. It’s about 06.30, so building work hasn’t started yet and it’s wonderfully quiet. I give a wide berth to a couple of penguins at the south end of the runway, and at the other I stop for a while to admire the view across North Cove with all its icebergs.

Penguins at the south end of the runway. (credits: ESA–I. Lawrence)

Thin pancake ice on the water in North Bay. (credits: ESA–I. Lawrence)

Looking down from the Dash the bergs look like tiny, insignificant, blobs of ice, but from the ground they dominate the landscape. They are constantly shifting and drifting, sometimes upturning to reveal their shiny scratched bellies, so the view is different every day here. The sun catches the sea surface and I spot some thin pancake ice near the shore.

Around lunchtime, Carl and Gaëlle leave in the Dash to under fly today’s CryoSat track over the Weddell Sea. I won’t be meeting them off the plane this time because we leave at 01:00 for the next flight. I head to bed after dinner and set my alarm for midnight. At least it will be light when I wake up…

12 December: Weddell Sea icebergs

We take off at around 01:00 local time and begin our journey to the Weddell Sea. The light is beautiful at this time, illuminating the mountains on the peninsula with a soft pink glow. Our route takes us past the trio of peaks Blaze, Hope and Glory. At 3200 metres high, Hope is the highest mountain on the Antarctic peninsula and technically, since it’s in British territory, UK?! I’m struck again by the sheer vastness of it all; snow-blanketed land stretching as far as the eye can see that nothing has ever set foot on, nor probably ever will.

Crossing the peninsula. (credits: ESA–I. Lawrence)

Our aim today is to fly northwards along a section of NASA’s ICESat-2 track as the satellite passes over, and then head east to meet a CryoSat track which we will follow south. Conditions in the Weddell Sea are clear and still, and we pootle along at 120 knots, our instruments measuring the sea ice 300 metres beneath us. We encounter some impressive tabular icebergs, like this one that our altimeter measured to be about 50 meters tall.

As we head southwards along the CryoSat ground track, we hit a large expanse of open water. It’s right in the middle of the Weddell Sea ice pack, so its presence is really puzzling. Alan, our pilot, who knows these waters well, guesses it’s due to a big iceberg that’s travelling north. The wind, which is slowly pushing the berg, picks up speed over its flat smooth surface and, at the other side, blows the sea ice away from its edge. Basically, a coastal polynya but at the ‘coast’ of an iceberg. We soon start to approach what looks like shelf – but we’re nowhere near land. Alan was right, it’s an iceberg, and it’s enormous, once we’re above it, it’s all we can see in every direction.

Large icebergs in the Weddell Sea. (credits: ESA–I. Lawrence)

Our journey home takes us over the Larsen-D ice shelf. I expected a vast expanse of solid ice, stretching all the way to the horizon where the peaks of the peninsula are visible. But it’s all broken up, disintegrated, nothing more now than a collection of huge icebergs waiting to drift north and eventually melt. These bergs are made of ice that’s thousands of years old – the shelf won’t be back any time soon.

Expanse of open water in the Weddell Sea ice pack in the leeside of an enormous iceberg visible in the distance. (credits: ESA–I. Lawrence)

Break-up of the Larsen-D ice shelf. (credits: ESA–I. Lawrence)

In the evening, we hear Alan on the radio saying he’s spotted some orca off North Beach. I’m in the office and at least 15 minutes away. I assume they’ll be gone by the time I get there. Ten minutes later he’s back on the radio saying that they are still there, hunting seal. I decide to make a dash for it. I bump into most of the base en-route doing the same. It turns out we didn’t need to rush; the orca remain in the bay for hours, a whole pod of them including calves.

Orca whale hunting in North Bay. (credits: ESA–I. Lawrence)

They swim and dive in unison to create a bough wave which washes the seals off the iceberg. This happens countless times; each time we assume that the seals are dead only for them to launch themselves back onto the iceberg minutes later. In the end, with cold toes and dinner beckoning, I head back to base without knowing the outcome, but I can’t imagine it ended well for the seals.

13 December: Cryo2ice orbit

Today is an important day, probably the most important of the campaign. We are targeting a ground track which is being flown simultaneously by both satellites, CryoSat and ICESat-2. Back in the summer, ESA adjusted the orbit of CryoSat so that it periodically aligns with ICESat-2, a manoeuvre called Cryo2ice (originally realised for the Arctic in 2020). The two satellites give us different information about sea ice, but because sea ice drifts, in their normal orbit configuration they are never looking at the same ice. Cyo2ice presents a unique opportunity to gather information from the two sensors over the same sea ice, and if we simultaneously under fly with the Dash we’ll have even more, higher-resolution information about that sea ice. An aircraft has never flown under a cryo2ice orbit before, so it will be a great achievement if we pull it off.

The team takes off in the Dash to coincide with the CRYO2ICE orbit over the Weddell Sea. (credits: ESA–I. Lawrence)

I’m not on the plane for this one; but I do manage to delay their take off by a few seconds because I’m standing too close to the runway and can’t hear my walkie-talkie – the tower telling me to get back. I wave off the Dash (from my newly-found safe distance) at around 13:00, and I later get word that they hit the mid-point of the Cryo2ice ground track exactly as planned, meaning that both ICESat-2 and CryoSat overflew them – hooray!

14 December: Up and away again

Another early morning flight – and an all-female crew other than Alan! Gaëlle and I decide to take shifts monitoring the instruments; she goes first and agrees to wake me up after a few hours. When she does finally wake me it’s 06:00 and we’re about to head back to Rothera. She says she wasn’t tired, but soon starts nodding off once I take over.

Because this journey has been relatively short compared to the others, we decide to use the remaining time (and fuel) to return to the Fuchs Piedmont and overfly the corner reflectors once more. In particular, we’re interested in whether we can see them with the radar in its high-altitude mode; operating at 700 rather than 300 metres. Unfortunately, when we arrive the whole island is enveloped in cloud and the visibility is too poor to fly the survey lines. At least I’m spared the motion sickness this time.

Feeling well-rested, I head back to our office to prepare my slides for the presentation we have been invited to give to everyone on base this evening. Fortunately, they have postponed tonight’s screening of Die Hard so we won’t be competing with Bruce Willis for an audience. Most people here are not scientists, there’s a huge team keeping this place going; plumbers, engineers, IT technicians, mechanics, chefs, doctors, to name but a few. Scientists like us come in and do stints of work, and during that time the staff at Rothera support them, so it’s only right that they get to hear what it is we’re actually doing.

Dash-7 crew for this morning’s flight. (credits: ESA–I. Lawrence)

The talk goes well, and we sit for a while taking questions from people before everyone heads to the bar. We haven’t put a flight plan in for tomorrow so Gaëlle and I grab a soft drink and head to the office to work out coordinates for our final survey flight tomorrow afternoon.

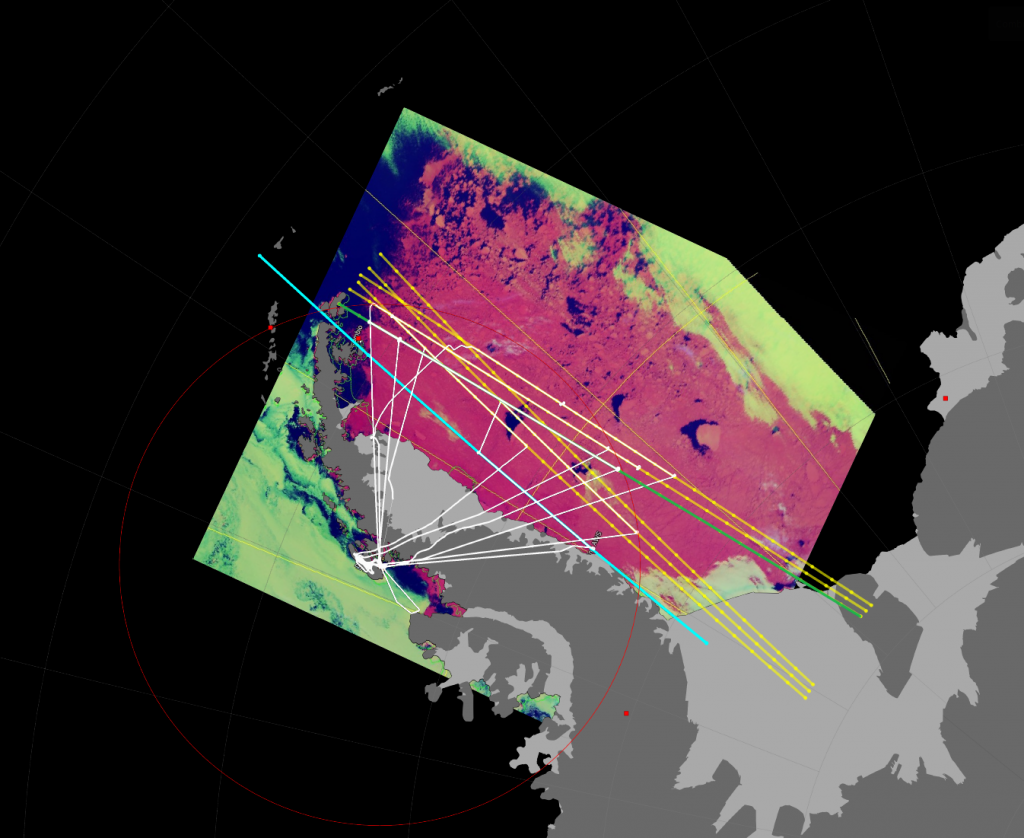

15 December: the end

Alan pops by the office after the morning’s Met Briefing to tell us that the weather at Rothera is too poor to fly today. So that’s it! All over! I feel disappointed (especially because I spent most of yesterday’s flight asleep), but I look again at the map of what we’ve done and remind myself what a successful campaign it’s been. These airborne campaigns are always at the mercy of the weather, and although the cloud has now finally found us, we’ve had almost a week of blue skies which is pretty much unheard of here. Even with good weather at Rothera, the Weddell Sea was likely to be full of cloud, so five survey flights in predominantly clear skies is really good going. And we hit the Cryo2ice orbit; it’s the first time one has even been simultaneously under flown, so that’s a real achievement.

Map of the tracks flown (white). In yellow are the ground tracks of the CryoSat satellite, cyan ICESat-2, and green is theCRYO2ICE orbit underflown on the 13 December 2023. Background image shows sea ice in pink, open water in blue and cloud in lime green. Large expanses of open water in front of large icebergs, like the one we flew over on 12 December are clearly visible. (credits: campaign team)

With no more flight planning to do, we head straight to the hangar to start derigging the plane. With only a couple of days until 15 of us need to get to Punta Arenas to make our flights back to the UK, there is a lot to do to convert the Dash back into a passenger jet.

16 December: dismount

More plane dismounting. Lots of cable ties….

Cable ties. (credits: ESA–I. Lawrence)

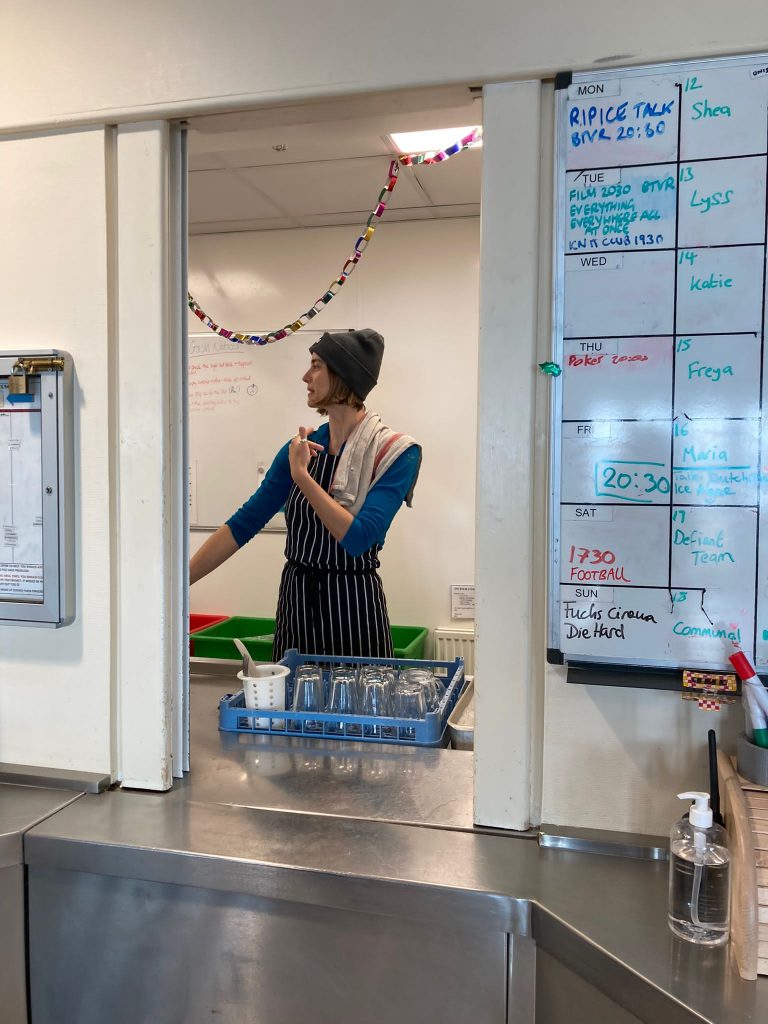

17 December: GASH duty

Today is our day on GASH. It’s an old military term broadly meaning ‘taking out the rubbish’. At Rothera it means helping out in the canteen; chopping veg, washing-up, cleaning up after meals, refilling condiment bottles etc.

Gaëlle and I helping in the kitchen. (credits: ESA–I. Lawrence)

Everyone on base is on the rota for GASH duty at some point, it’s usually a whole day’s work for one person, but we divide the day into smoko, lunch and dinner and work in pairs. After being hosted so comfortably for the last ten days it’s only right we do our bit, and it’s the best place to see everyone on our last day.

The washing up area. (credits: ESA–I. Lawrence)

View of the dining room from the kitchen. (credits: ESA–I. Lawrence)

Mopping the office after Saturday dinner. (credits: ESA–I. Lawrence)

After dinner, and a quick mop down of the office we’ve occupied, we head to the bar. One last chance to beat Rob at pool… nope. Some beers and some darts, goodbyes, and then to bed. Tomorrow we begin our long journey back home….

This was a joint campaign between ESA and the UK-led DEFIANT project

Post from Isobel Lawrence (ESA).

Read news story on the ESA website: Future-proofing ice measurements from space

Discussion: no comments