In his next post, Gavin Tilstone from the Plymouth Marine Laboratory, describes the next leg of the voyage through the Atlantic for the AMT4OceanSatFlux project. Supported by ESA, the project the measures the flux of carbon dioxide between the atmosphere and the ocean using a state-of-the-art eddy covariance technique along the length of the Atlantic Ocean. These measurements will be used to validate a range of satellite products to gain regional and global estimates of gas exchange between the atmosphere and ocean.

From the 19 October 2019, we continued to steam southwest navigating through waters deeper than 4500 m. The journey took us parallel to the Bay of Biscay where the waters are 16°C and the surface greenness from phytoplankton is patchy and stringy. Before the mid- day sampling station, the blow from a fin whale was sighted off the starboard aft. As we continued south, the maximum phytoplankton Chlorophyll-a concentration deepened from 55 to 80 meters. This is akin to trekking into a large canyon or going deeper into the abyss.

After four days we were in sight of the Azores; strange to have land in view again. In the darkness of 05:00 the silhouette of Sao Miguel rose from the ocean, jewelled with street lights, cloven in trees and crowned with flattened peaks. The majority of Ponta Delgada still sleeping as were many of the scientists on the ship, as they rocked to and fro with the lap of Portuguese waters around the hull. As the sun rose at 07:00, it revealed the island’s patchwork of green, climbing majestically from the water’s edge. With the rising sun the sleeping town and ship become increasingly active.

The Azores from RRS Discovery. (PML)

The ship waited in the shadow of the islands, whilst both scientists and crew buzzed with excitement of adventure to find out what was in store, for some, on these undiscovered shores. In range of land again, mobile phone masts made the instant connection to the outside world with love ones, family and friends. Scientists and mariners alike craned over tiny screens, like herons staring into murky ponds, looking for food beneath the surface in the form of WhatsApp, Facebook, Snapchat and Messenger.

We were met by the pilot at 10:00 who guided us effortlessly to the dock to meet a cruise liner and cargo ships off loading maize to trucks on the buzzing quay. A foot on solid ground again, but still everything swaying in motion as though we were still at sea. A few of us scoured the streets for a backup refrigeration unit. In our experiments we use them to cool surface seawater to the temperature at depth (our existing ones had been struggling with the rising temperatures as we tracked south).

There are nine major Azorean islands clustered together into three main groups that extend for more than 600 km in a northwest–southeast direction. The islands were active volcanoes, of which the Island of Pico is the highest point at 2351 m. If measured from their base at the bottom of the ocean to their peaks, which thrust high above the surface of the Atlantic, the Azores are actually some of the tallest mountains on the planet.

The archipelago of the Azores is believed to have been discovered around 1427 by Portuguese navigator Diogo de Silves, who landed on the islands of Santa Maria and Sao Miguel. Five years later, Goncalo Velho Cabral and 12 crew disembarked on Santa Maria. By 1439, settlers, who were mainly from the Algarve region of Portugal, began to inhabit the islands. Over the next decade, the largest island, Sao Miguel, having fertile soil, further attracted Portuguese and French families to colonise it. The production of wheat, sugar cane, and oranges then led to economic growth and further population expansion. By the turn of the 17th century, Sao Miguel had become a major hotspot for battling European pirates before it eventually fell into the hands of the Spanish. It returned to Portuguese rule in 1640 when Ponta Delgada was named the capital of the Azores and became the main economic hub due to its strategic location on the coast. Many early seafarers and navigators used the Azores as a trading and stocking point before long journeys ahead to the Southern Ocean.

In a similar way, RRS Discovery had called into the Azores to refuel. The ship carries enough fuel for 55 days at sea steaming at an average of 10 knots. The fuel is not just used to power the engines, but a third of it is used to generate electricity and to make water. Ten tonnes of water is generated per day for both domestic and operational needs.

Dolphins on the bow. (PML)

A brief visit to the beach to sit on the blackened ash sands of San Roque and a refreshing dip in Atlantic waters, and we were back on the ship. As we pulled out of the dock, a tug gave as a naval water salute, firstly like an elephant cools itself in the baking African heat, but then like a Royal fountain. Then as we navigated away from the Ponta Delgada, common dolphins joined the ship, effortlessly weaving in and out of the surf created by the bulbous bow. It was an incredible sight as dorsal fins majestically drew white caps on the sea surface. Rolling and a turning and the occasional circus jump in redemption against the ring masters command. They stayed with us a while, jumping and frolicking in the surf and peeled away before sunset.

A large group of spectators of crew and scientists gathered to witness the green flash as the sun dips below the horizon before the dwindling light is swallowed by the night.

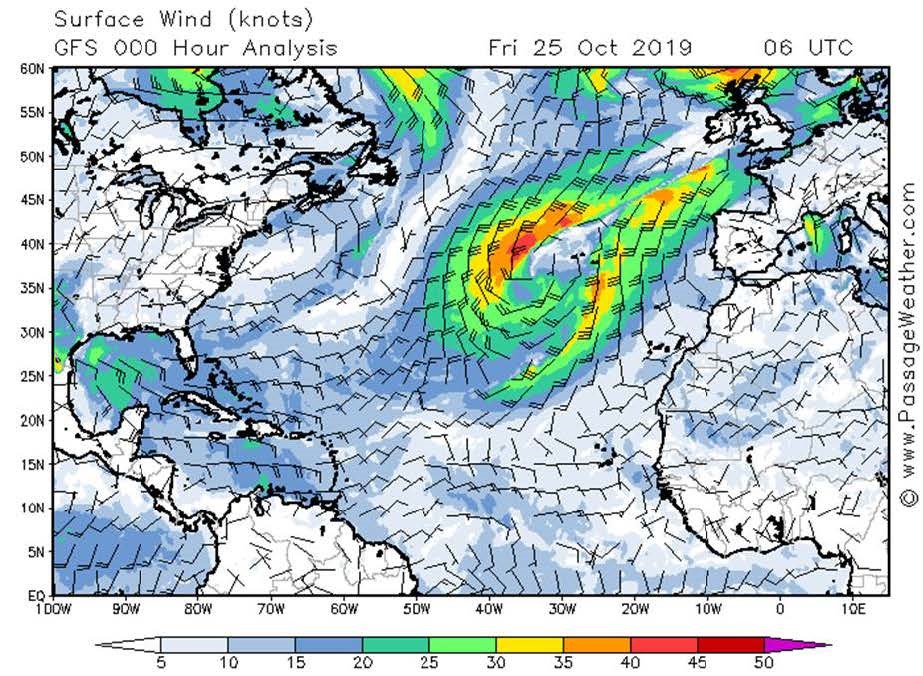

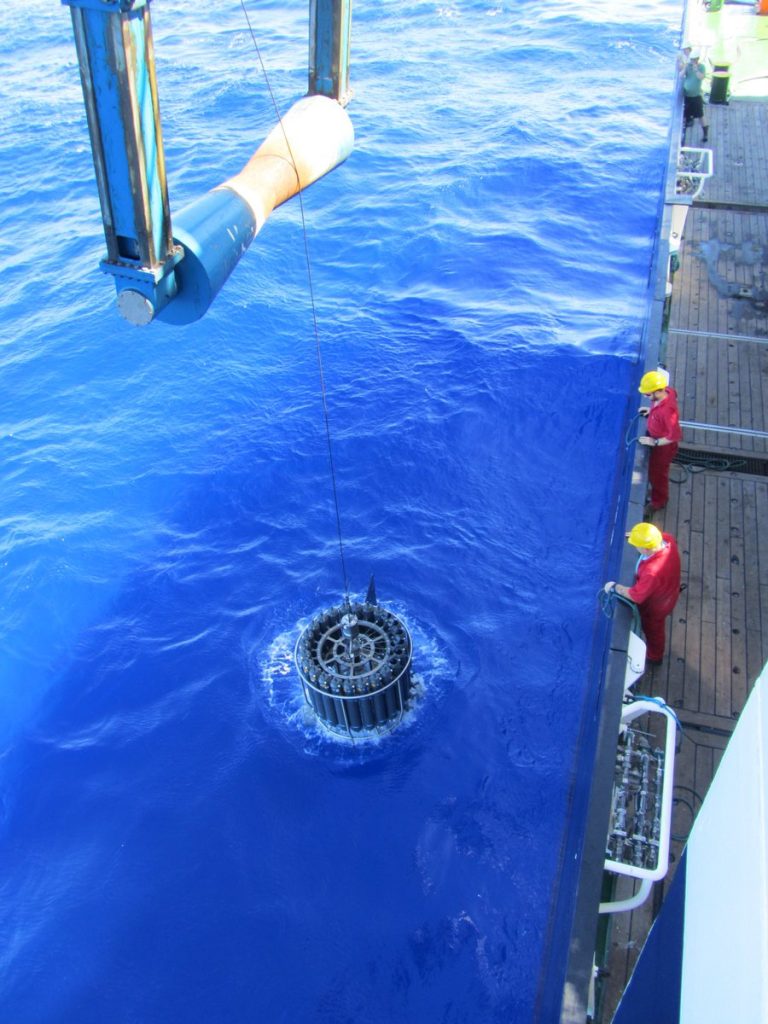

That night I was once again jolted awake by sudden and sometimes violent rolls of the ship. Like an innocent bystander being dragged into a brawl, we were caught up in yet another storm that was not my fight. Measuring force 6 on the Beaufort scale and 35 knot wind, swell to the beam and wind to the starboard bow put the sea into the mixer, and made for another lumpy night’s sleep. The morning station was cancelled. The swell and the wind meant that it was too dangerous to risk deploying the rosette sampler, which would have made like a 1.5 tonne church bell clanging against the side of the ship, putting the crew in danger and at risk of getting injured in recovering it.

Stormy waters. (PML)

Through the storm we moved further southwest and deeper into the North Atlantic Gyre. A gyre is a swirling vortex, which in the ocean is created by wind or currents. There are two main gyres in the Atlantic Ocean, which are created by currents; one in the north and one in the south. The Northern Gyre circulates clockwise and is created by the North Equatorial and North Atlantic currents. The North Atlantic Gyre extends from approximately 38°N to 19°N. Phytoplankton, tiny microscopic marine algae, reside in the twilight zone of the gyre since the light is too bright and their cells can burst and the nutrients that it requires for growth reside at depth.

Caught in a storm. (PML)

Phytoplankton of the Northern Gyre fix approximately 1.12 Gt carbon per year. As we tracked south, the mixed layer deepened to 80 meters and the phytoplankton biomass resided at between 130m.

Rosette sampler in the blue waters of the Northern Gyre. (PML)

Post from Gavin Tilstone, Plymouth Marine Laboratory

Discussion: no comments