We are transiting the deep ocean gyres, where life survives on the edge. From the surface of these deep blue waters there seems to be little life, except for the occasional flying fish skating out of the path of the ship.

Flying fish in the North Atlantic Gyre. (Credits: Ian Brown, Plymouth Marine Laboratory, UK).

At a greater depth, however, where only a fraction of the surface light penetrates, there dwells a multitude of diverse organisms that are sustained by bacteria. These organisms are photosynthetic and known as the Cyanobacteria. 100 metres deep, they live on recycled nutrients that are the waste products from other organisms, and form the essential macro- and micro-nutrients for them to exist where few other organisms can survive.

Ancestrally, through oxygenic photosynthesis, the Cyanobacteria were thought to have converted Earth’s un-inhabitable and hostile atmosphere into an oxygen rich one, which allowed a diverse range of life forms to colonise the planet. The chloroplasts of plants are thought to have evolved from Cyanobacterial via endosymbiosis.

Cyanobacteria can be found in almost every terrestrial and aquatic environment from the deep oceans, fresh water and terrestrial wet soils, to the dew that moisten rocks of the desert. Aquatic cyanobacteria are probably best known for extensive blue-green blooms that can be toxic in lakes and rivers.

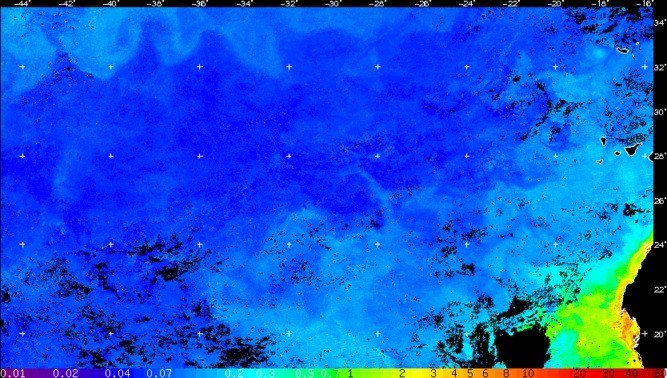

Chlorophyll-a median composite from 27 September to 03 October 2017. (Image processed by Silvia Pardo for the NERC National Earth Observation Data Analysis and Archive Service at Plymouth Marine Laboratory).

In the ocean, Cyanobacteria fulfil a vital ecological role through the fixation of carbon and nitrogen which makes a significant contribution to global nutrient budgets. Through photosynthesis, Cyanobacteria convert solar energy into biomass at a rate of ~450 TW and therefore account for 20–30% of Earth’s photosynthetic productivity.

Out here on this blue slab of water where chlorophyll concentrations are low (~0.05 mg m-3), colonial Cyanobacteria known as Trichodesmium are also commonly found in this surface layer.

They occur as finely interwoven mats of spikey filaments known as trichomes. This phytoplankton has a huge impact on the marine ecosystem as it fixes nitrogen from the atmosphere and pulls it down into the sea to fertilise the surface layer with this essential macro-nutrient.

This process accounts for about half of the total N2-fixation in the global ocean. In some parts of the world these mats are so vast that they can be detected directly the Copernicus Sentinel satellites.

Trichodesmium thiebautii from surface haul nets (Credits: Erica Goetze, University of Hawaii, USA; Katjia Peijnenburg, Deborah Wall-Palmer & Lissette Mekkes, Naturalis Biodiversity Centre, Leiden, The Netherlands).

Post from Gavin Tilstone (PML)

Discussion: no comments